Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio is higher than any other developed country. Yet somehow, this economic giant continues to thrive while other nations with far less debt struggle with financial crises.

How is this possible? Let’s dive deep into Japan’s extraordinary debt story and uncover the secrets behind this economic paradox.

The Shocking Scale of Japan’s Debt

Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio stands at a staggering 263%. This means Japan owes more than 2.6 times what its entire economy produces in a year.

To put this in perspective, imagine if your annual salary was $50,000, but you owed $130,000 in debt. That’s the equivalent of Japan’s situation.

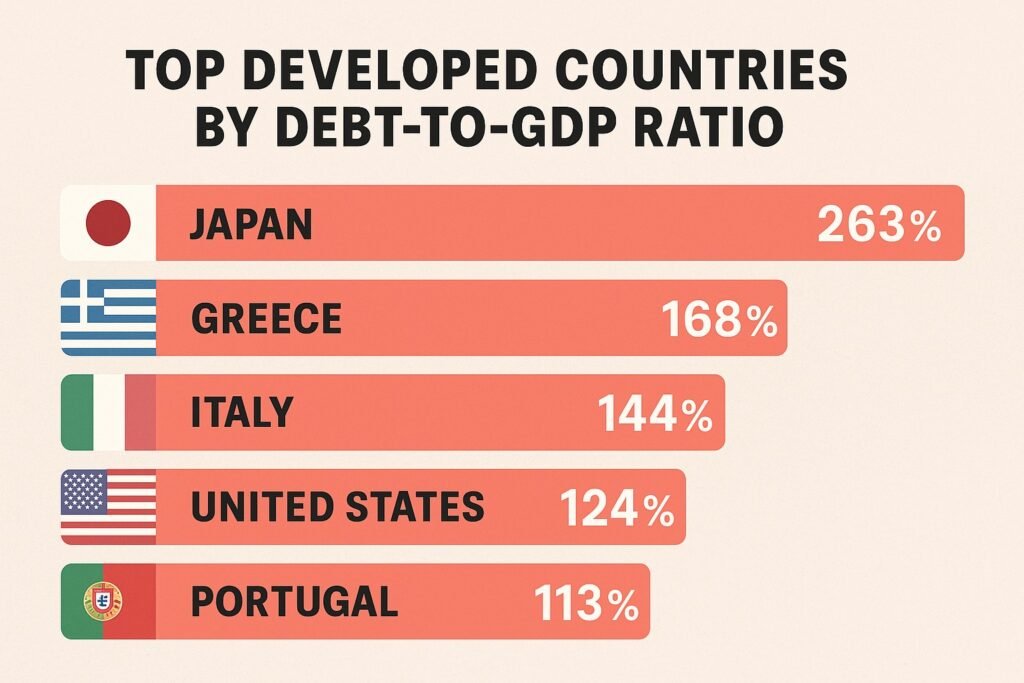

How Japan’s Debt Compares to Other Nations

Here’s how Japan stacks up against other major economies:

- Japan: 263% debt-to-GDP ratio

- Greece: 168% (faced severe financial crisis in 2010s)

- Italy: 144% (struggles with economic instability)

- United States: 124% (considered manageable but concerning)

- Germany: 65% (considered healthy)

Despite having double the debt ratio of crisis-hit Greece, Japan hasn’t experienced a market crash, sovereign default, or needed an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout.

The Origins: How Japan Built This Mountain of Debt

The Bubble Economy and Its Dramatic Collapse (1980s-1990)

In the 1980s, Japan experienced one of history’s most spectacular economic bubbles. Real estate and stock market prices soared, fueled by easy money and unchecked speculation.

Several key factors contributed to the formation of the bubble:

- Loose monetary policy: After the 1985 Plaza Accord, Japan cut interest rates to avoid a yen appreciation, flooding the economy with cheap credit.

- Financial deregulation: Banks were newly empowered to lend more aggressively, especially to real estate and equities.

- Speculative frenzy: Investors, corporations, and even households believed land and stock prices would rise indefinitely. Tokyo real estate was so inflated that the land beneath the Imperial Palace was once valued higher than all the property in California.

- Cultural overconfidence: Many believed Japan’s economic model was unbeatable, feeding a national narrative of permanent growth and prosperity.

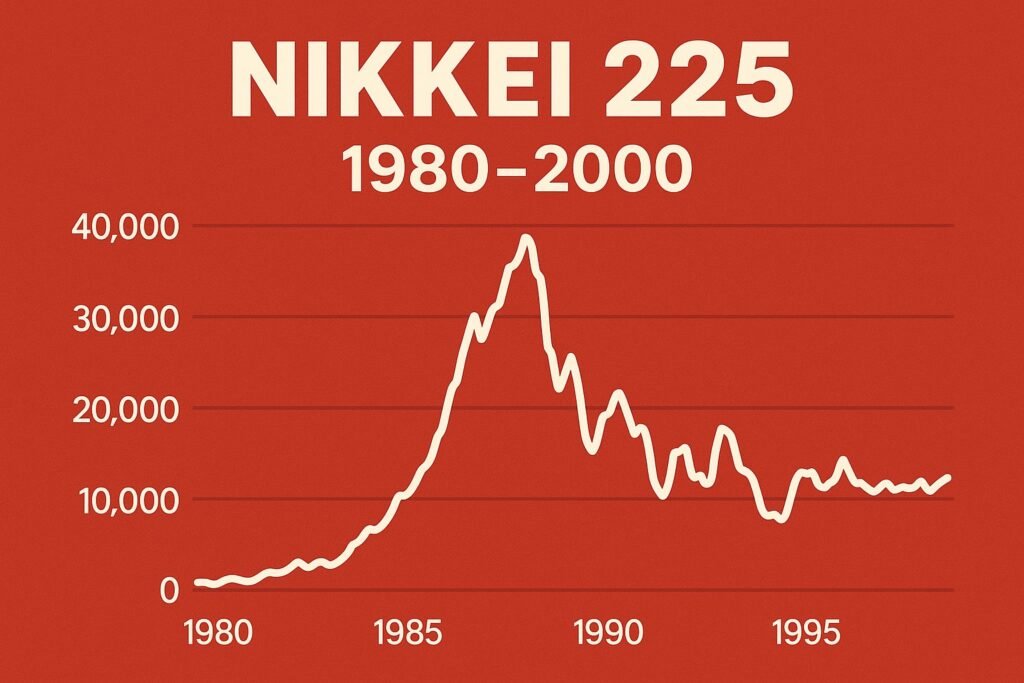

The Nikkei 225 index, Japan’s primary stock index, surged to nearly 39,000 points in December 1989, and land prices in Tokyo’s commercial districts increased more than 500% in a decade.

The bubble burst in 1990, and the consequences were devastating:

- The Nikkei 225 plummeted 80% from its peak

- Commercial land prices in major cities fell by 70%

- Banks were left holding trillions of yen in bad loans

- Major corporations faced bankruptcy

The Government’s Response: Spend to Save

Faced with economic collapse, the Japanese government made a crucial decision: spend massively to prevent a complete meltdown.

The stimulus strategy included:

- Infrastructure projects: Building roads, bridges, and public facilities

- Bank bailouts: Rescuing failing financial institutions

- Tax cuts: Putting more money in citizens’ pockets

- Social spending: Supporting unemployed workers

While these measures prevented total economic collapse, they came at an enormous cost. The government borrowed heavily to fund these programs, and debt began accumulating rapidly.

The Lost Decades: When Growth Disappeared

Between 1991 and 2020, Japan’s economy grew at an average rate of just 0.8% per year. For comparison, the United States averaged around 2.5% growth during the same period.

This weak growth created a vicious cycle:

- Slow growth meant lower tax revenues

- Lower revenues forced more government borrowing

- More borrowing added to the debt burden

- High debt limited future spending options

The Demographic Time Bomb

Japan faces a unique demographic challenge that makes its debt situation even more complex.

The aging crisis by the numbers:

- 30% of Japanese citizens are over 65 years old

- Birth rate: 1.3 children per woman (well below replacement level)

- Population decline: Japan loses about 400,000 people annually

This demographic shift creates financial pressure because:

- More elderly people need pensions and healthcare

- Fewer working-age people pay taxes

- Healthcare costs rise as the population ages

- Social security obligations grow every year

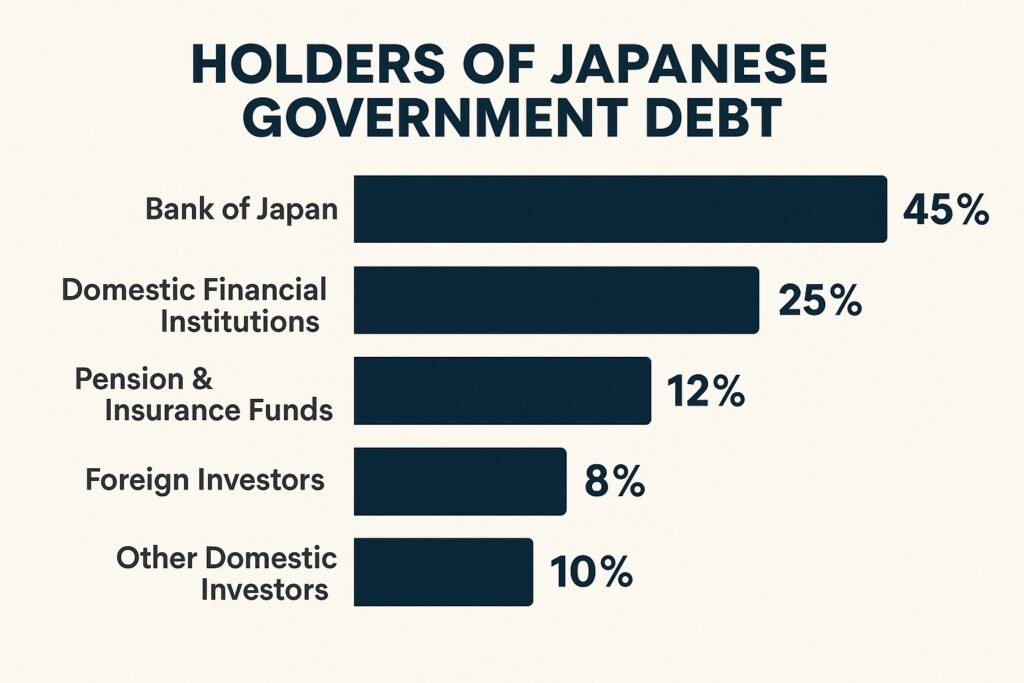

The Mystery: Who Buys All of Japan’s Debt?

Here’s where Japan’s story becomes truly unique. Unlike most heavily indebted countries, Japan doesn’t rely on foreign investors to buy its government bonds.

Japan’s Debt Ownership Breakdown (2024):

- Bank of Japan (Central Bank): 45%

- Domestic institutions (pension funds, insurance companies, banks): 37%

- Foreign investors: Less than 10%

- Japanese households and others: 10%

Why Domestic Ownership Matters

When a country owes money primarily to its own citizens and institutions, it faces different risks than countries dependent on foreign creditors.

Advantages of domestic debt ownership:

- No risk of sudden capital flight during crises

- Less vulnerability to currency attacks

- Greater policy flexibility during economic downturns

- Reduced exposure to international market sentiment

Compare this to other countries:

- Argentina: Heavy foreign debt led to multiple defaults

- Turkey: Foreign currency debt caused severe currency crises

- Greece: Foreign-held debt complicated bailout negotiations

The Bank of Japan’s Critical Role in Japan’s Debt

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has become the ultimate buyer of government debt through unprecedented monetary policies.

Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) Explained

Since 2013, the BoJ has implemented an aggressive bond-buying program:

- Monthly purchases: The BoJ buys approximately ¥6 trillion in government bonds monthly

- Total holdings: Over ¥600 trillion in government bonds (about $4 trillion)

- Market impact: This massive buying keeps interest rates artificially low

How this works in simple terms:

- Government issues new bonds to fund spending

- BoJ creates new money electronically

- BoJ uses this new money to buy government bonds

- This keeps bond prices high and interest rates low

- Government can continue borrowing cheaply

Five Pillars Supporting Japan’s Debt Mountain

Despite the enormous debt load, Japan hasn’t collapsed due to five key factors:

1. Sovereign Currency Control

Japan issues debt in yen, its own currency. This gives Japan a crucial advantage:

- Printing power: Japan can theoretically print yen to pay debts

- No foreign exchange risk: Debt doesn’t become more expensive if the yen weakens

- Monetary policy flexibility: The BoJ can adjust interest rates independently

Countries that borrow in foreign currencies (like dollars) lack this flexibility.

2. Ultra-Low Interest Rates

Japan’s borrowing costs are among the lowest in the world:

- 10-year government bond yield: Approximately 0.8%

- Historical context: Rates were near zero or negative for two decades

- Servicing costs: Low rates mean debt is cheap to maintain

Cost comparison example:

- If Japan paid 3% interest (normal for many countries): ¥36 trillion annually

- At current 0.8% average rate: Less than ¥10 trillion annually

- Savings: Over ¥25 trillion ($175 billion) per year in interest costs

3. Deflationary Environment

While most countries worry about inflation, Japan has battled the opposite problem: deflation and extremely low inflation.

Japan’s inflation history:

- 1990-2020 average inflation: Under 1% per year

- Several periods of actual deflation (falling prices)

- Current inflation: Around 2% (considered high for Japan)

Why low inflation helps with debt:

- Real debt burden doesn’t grow from price increases

- Investors accept lower returns in low-inflation environments

- Government spending maintains purchasing power

4. Institutional Trust and Political Stability

Japan has never defaulted on its debt in modern history. This creates a virtuous cycle:

- Historical reliability: Investors trust Japan will always pay

- Strong institutions: Rule of law and property rights are well-established

- Political predictability: Policy changes happen gradually

- Credit rating: Japan maintains investment-grade ratings despite high debt

5. Cultural Investment Preferences

Japanese savers have unique characteristics that support government bond markets:

Japanese investor behavior:

- Risk aversion: Prefer safety over high returns

- Domestic bias: Favor familiar Japanese investments

- Long-term focus: Don’t panic during market volatility

- Aging population: Retirees prioritize capital preservation

This creates steady demand for Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) even at very low yields.

The Hidden Costs of Japan’s Debt Strategy

While Japan has avoided crisis, its debt strategy has created significant long-term problems:

Economic Stagnation

Japan’s economy has underperformed for decades:

- GDP per capita growth: Among the slowest in developed world

- Productivity growth: Lags behind other G7 nations

- Innovation metrics: Declining in global competitiveness rankings

- Living standards: Real wages have stagnated for 20+ years

The Debt Trap Dilemma

High debt levels limit policy options:

- Fiscal constraints: Limited room for new spending programs

- Reform paralysis: Can’t cut spending without economic backlash

- Political deadlock: Elderly voters resist benefit cuts or tax increases

Bank of Japan’s Growing Risks

The BoJ’s massive bond holdings create new vulnerabilities:

- Balance sheet risk: ¥600+ trillion in bonds could lose value if rates rise

- Exit strategy problems: Difficult to unwind massive positions

- Inflation risks: If inflation rises, bond values could collapse

- Independence concerns: BoJ effectively finances government spending

Interest Rate Sensitivity

Japan’s debt burden is extremely sensitive to interest rate changes:

Scenario analysis:

- 1% rate increase: Additional ¥5 trillion ($35 billion) in annual interest costs

- 2% rate increase: Additional ¥10 trillion ($70 billion) in annual costs

- 3% rate increase: Interest payments could consume 15%+ of government budget

Can Other Countries Copy Japan’s Debt Model?

Many economists and policymakers wonder if Japan’s approach could work elsewhere. The answer is complicated.

Requirements for Japan’s Model

| Factor | Japan | United States | European Union |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borrows in own currency | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | ⚠️ Partially |

| High domestic savings | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | ⚠️ Varies |

| Low inflation expectations | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | ⚠️ Mixed |

| Cultural bond preference | ✅ Yes | ❌ No (stocks preferred) | ❌ No |

| Central bank bond buying | ✅ Massive scale | ⚠️ Limited scale | ⚠️ Constrained |

| Political stability | ✅ Yes | ⚠️ Polarized | ⚠️ Fragmented |

Why Most Countries Can’t Replicate Japan’s Debt Situation

United States challenges:

- Higher foreign debt ownership (25%+ vs Japan’s <10%)

- Recent inflation surge broke low-inflation expectations

- Cultural preference for stock market over bonds

- Political system makes consistent policy difficult

European Union challenges:

- No unified fiscal policy across eurozone

- Different countries have different debt situations

- European Central Bank has limited mandate

- Higher inflation expectations historically

Emerging market challenges:

- Often must borrow in foreign currencies

- Less developed domestic bond markets

- Higher inflation and political instability

- Lower investor trust in institutions

Future Scenarios: Japan’s Debt.. What Happens Next?

Japan faces several possible futures, each with different implications:

Scenario 1: Continued Muddling Through

What it looks like:

- Debt continues growing slowly

- BoJ maintains ultra-low rates

- Economy grows at 0-1% annually

- Demographics continue deteriorating

Probability: Moderate to high Risks: Gradual decline in living standards, loss of global competitiveness

Scenario 2: Successful Reform and Revival

What it looks like:

- Productivity reforms boost growth

- Immigration increases working-age population

- Gradual debt reduction through higher growth

- Successful exit from ultra-low rates

Probability: Low to moderate Requirements: Major political and social changes

Scenario 3: Crisis and Forced Adjustment

What it looks like:

- Rising inflation forces BoJ to raise rates

- Bond market instability

- Sharp fiscal adjustment required

- Potential currency crisis

Probability: Low but increasing Triggers: External inflation shock, loss of confidence, demographic collapse

Lessons for Other Nations

Japan’s experience offers important insights for other heavily indebted countries:

What Japan Did Right

- Maintained institutional credibility: Never defaulted, kept strong rule of law

- Controlled the narrative: Avoided panic through consistent communication

- Leveraged domestic savings: Reduced dependence on foreign creditors

- Used monetary policy creatively: BoJ innovations kept system stable

What Japan Struggled With

- Delayed necessary reforms: Avoided painful but needed structural changes

- Demographics ignored too long: Failed to address aging population proactively

- Productivity stagnation: Didn’t invest enough in innovation and efficiency

- Political paralysis: Short-term thinking prevented long-term solutions

Conclusion: Is Japan’s Debt A Controlled Fire or Slow-Motion Crisis?

Japan represents one of the most fascinating economic experiments in modern history. The country has managed to carry an unprecedented debt load without experiencing the crashes that economic textbooks predict.

Japan’s success factors:

- Unique combination of domestic savings, institutional trust, and monetary control

- Cultural factors that support low-return, high-safety investments

- Central bank willing to take extraordinary measures

- Patient population that accepts low growth for stability

The price of stability:

- Three decades of economic stagnation

- Declining living standards relative to other developed nations

- Limited policy flexibility for future challenges

- Growing risks from demographic change

The ultimate question: Is Japan a master of crisis management, or is it simply experiencing the world’s longest, slowest-moving financial crisis?

The answer may determine not just Japan’s future, but provide crucial lessons for other aging, heavily indebted societies around the world.

As global debt levels continue rising and populations age in many developed countries, Japan’s experience—both its successes and failures—becomes increasingly relevant for understanding the future of government finance in the 21st century.

Only time will reveal whether Japan’s approach represents sustainable fiscal management or merely the postponement of an inevitable reckoning.