Apple is one of the world’s most valuable companies, trading the top market-cap spot with Microsoft, Google, and Nvidia. But Apple isn’t just famous for iPhones and MacBooks. Behind the scenes, it has mastered a very different kind of design: designing its tax bill.

At the center of Apple’s tax savings story is Ireland, a small country that became the unlikely hub of one of the world’s biggest corporate tax strategies.

How Apple Used Irish Subsidiaries to Book Global Profits

Here’s the part most people miss: Apple didn’t just move a factory to Cork. It built a network of Irish subsidiaries that allowed it to book profits from sales made all around the world—as if they had been earned in Ireland.

Why does that matter? Because for decades Ireland offered one of the lowest corporate tax rates in the world—12.5% compared to the old U.S. rate of 35% (before Trump cut it to 21%).

This is how it worked:

-

Intellectual Property (IP) transfers – Apple shifted ownership of patents, software rights, and trademarks to Irish entities.

-

Licensing fees – Subsidiaries in other countries paid Apple Ireland royalties to use that IP.

-

Profit funneling – The royalties and sales profits piled up in Ireland, where they were taxed at Irish rates—or sometimes hardly taxed at all.

A U.S. Senate investigation revealed that one Irish subsidiary reported $22 billion in profit in 2011 but paid only $10 million in tax—an effective rate of 0.05%.

Leprechaun Economics: When GDP Becomes a Joke

In 2015, Ireland’s GDP suddenly jumped 26.3% in a single year. Nobel Prize–winning economist Paul Krugman called it “leprechaun economics.”

Why? Because Apple shifted massive amounts of its intellectual property to its Irish subsidiaries that year. Overnight, Ireland’s economic data looked inflated.

Here’s the reality:

-

Ireland’s GDP per capita (2023): ~$110,000

-

Ireland’s GNI per capita (2023): ~$60,000

That $50,000 gap reflects how companies like Apple boost GDP on paper, without creating equivalent income for Irish households.

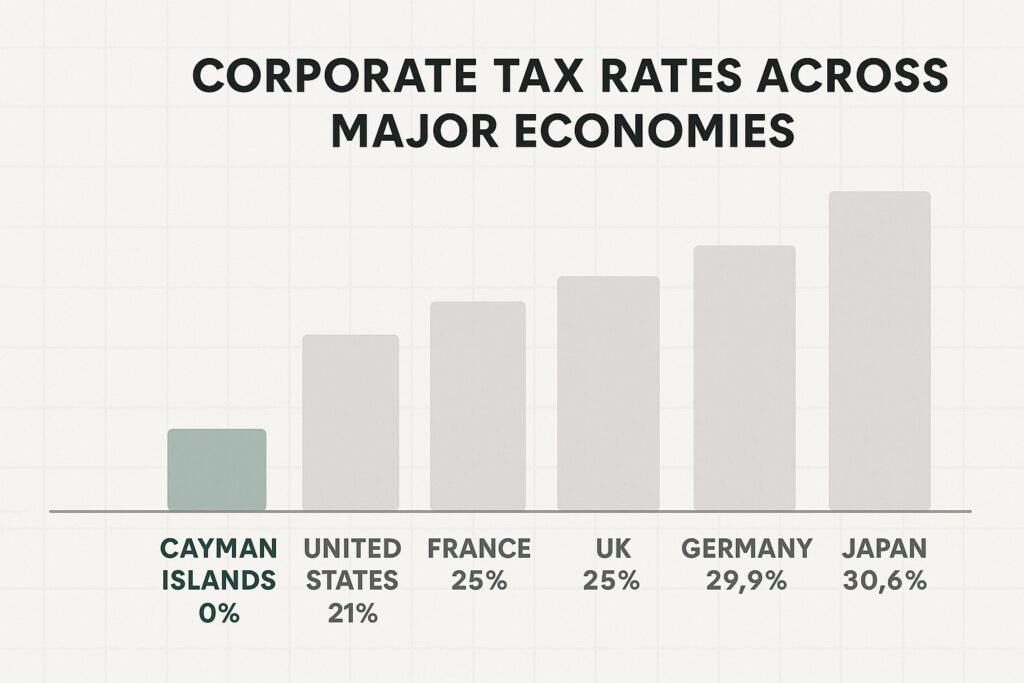

Why Ireland and Not the Caymans or UAE?

At first glance, Apple could have booked profits in places with even lower taxes—like the Cayman Islands (0% corporate tax) or the United Arab Emirates (historically 0%, now 9%). But here’s why Ireland was the obvious choice:

-

Legitimacy within the EU – Ireland is a full EU member, which means Apple’s Irish subsidiaries enjoy the legal protections, treaties, and credibility of being inside the European single market. A Cayman or UAE structure would look like a blatant “tax dodge” and invite regulatory backlash.

-

Market Access – Ireland gave Apple a legal way to funnel profits while maintaining a real European headquarters. From Cork, Apple could sell across the EU seamlessly under single-market rules—something a Caribbean shell company could never do.

-

Government Cooperation – Ireland’s 12.5% corporate tax (now 15% under OECD rules) struck a sweet spot: low enough to attract Apple, but high enough to look legitimate compared to “blacklist” jurisdictions. Ireland also tailored its tax code to accommodate IP transfers and royalty structures.

-

Talent & Infrastructure – Unlike pure havens, Ireland offered a skilled workforce, EU-level infrastructure, and the optics of “real operations” to justify profits being booked there.

In short: Apple needed both low taxes and legitimacy. Ireland gave it both.

The EU’s $14.5 Billion Case Against Apple

In 2016, the European Commission concluded that Apple had received illegal tax benefits from Ireland. It ordered Apple to pay €13 billion ($14.5 billion) in back taxes.

Ireland and Apple appealed, arguing that Ireland applied its own laws consistently. As of 2025, the case is still unresolved.

To show scale: €13 billion is nearly the size of Ireland’s entire health budget.

Apple’s Tax Savings in Perspective

Apple’s savings aren’t small change. Over the last two decades:

-

2009–2012: Avoided roughly $44 billion in U.S. taxes.

-

Mid-2010s: Built up over $200 billion in offshore cash, largely in Ireland.

-

Annual impact today: With an effective tax rate of ~16% vs. the U.S. 21% rate, Apple saves $4–6 billion every year.

Cumulatively, Apple’s tax savings exceed $100 billion—more than the GDP of countries like Slovakia or Ecuador.

📊 Visual placement: Line chart – Apple’s effective tax rate vs. U.S. statutory rate, 2000–2025.

The Impact on Ireland

Apple isn’t just a tenant in Ireland—it’s one of the single biggest corporate taxpayers in the country. Analysts estimate Apple may account for a double-digit share of Ireland’s corporate tax receipts, possibly approaching a quarter in some years, though the government doesn’t release company-specific data.

This dependence has three major consequences:

-

Revenue risk: If Apple ever restructures, Ireland could lose billions overnight.

-

Distorted statistics: Ireland looks richer on paper than its citizens feel in reality.

-

Policy vulnerability: Global tax reforms, like the OECD’s 15% minimum tax, directly target Ireland’s model.

In 2022, Ireland’s finance ministry admitted that corporate tax revenues were “unsustainably concentrated” in a handful of tech giants.

Apple’s Tax Savings: The Multinational Playbook

Apple is the poster child, but it’s not the only player:

-

Google/Alphabet: Long used the “Double Irish, Dutch Sandwich” strategy to route global ad revenues through Ireland and the Netherlands.

-

Microsoft: Shifted more than $50 billion in profit to Ireland in 2020, avoiding billions in U.S. taxes.

-

Pfizer: Has major Irish operations and benefits from low-tax IP arrangements, especially for its blockbuster drugs.

In fact, the top 10 multinationals in Ireland—mostly U.S. tech and pharma—are responsible for over half of the country’s corporate tax revenue.

Why It Matters Globally

Apple’s Irish strategy highlights a larger problem: tax codes built for a 20th-century world can’t keep up with 21st-century digital giants.

-

For investors: Apple’s tax efficiency boosts profits and stock returns.

-

For governments: It erodes the tax base, shifting the burden to smaller businesses and individuals.

-

For Ireland: It creates a dangerous dependency on companies that could leave with the stroke of a pen.

The OECD’s 15% global minimum tax is meant to close these loopholes—but as history shows, corporations and their accountants are always one step ahead.

Conclusion: Apple’s Other Masterpiece

Apple reinvented the smartphone. But it also reinvented tax planning. By using Irish subsidiaries to claim global profits, Apple has saved well over $100 billion in taxes—transforming not only its own balance sheet but also Ireland’s entire economy.

For shareholders, that’s a win. For Ireland, it’s both a blessing and a vulnerability. And for the rest of the world, it’s a reminder that in today’s economy, tax strategy can be as powerful as technology itself.