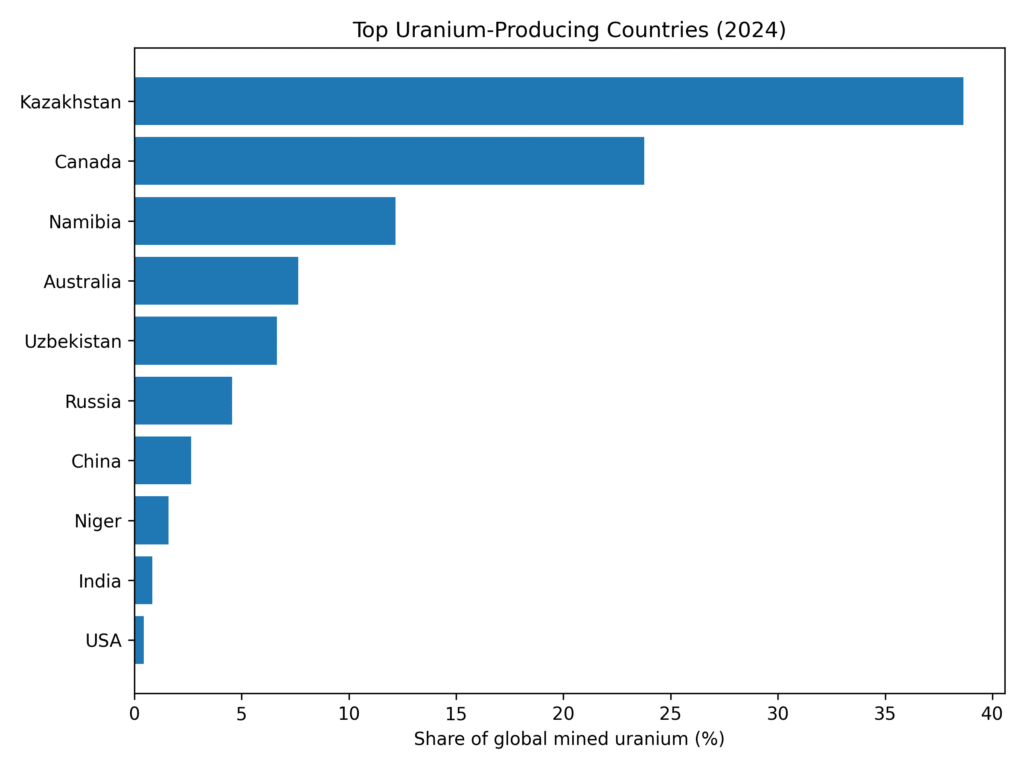

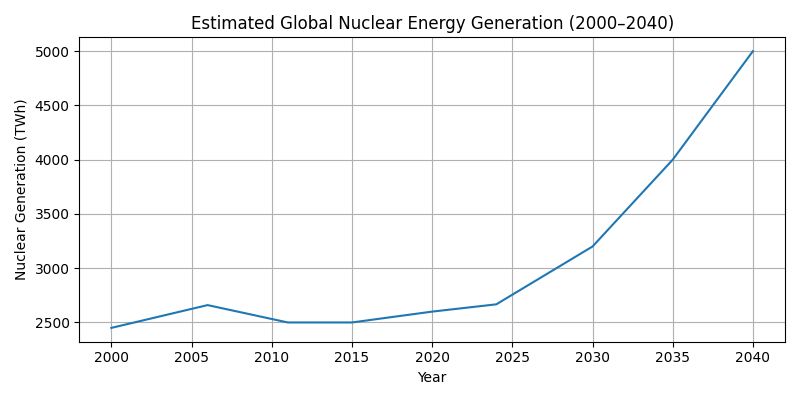

The nuclear revival is built on a paradox. A resource needed for the world’s energy transition comes from a handful of mines. In 2024 Kazakhstan’s in‑situ leach fields supplied 39 % of the world’s mined uranium. That figure is more than Canada and Namibia combined [1]. Early 2025 data show the share hovering around 38 %, with output growing roughly 10 % year‑on‑year [2]. Governments are dusting off reactor plans. Global nuclear capacity stood at 398 gigawatts (GWe) in June 2025, and 71 GWe of new capacity was under construction [3]. The World Nuclear Association projects capacity will climb to 746 GWe by 2040 [3]. This surge implies a steep rise in demand. Why does a landlocked country of 20 million people dominate such a strategic material? And what happens when rising demand collides with a supply chain bottlenecked by a single region?

Kazakhstan’s edge: geology, scale and strategy

Kazakhstan’s advantage begins underground. In the 1970s Soviet geologists pioneered in‑situ leach (ISL) mining in the country’s porous sandstones. Instead of blasting open pits, operators inject acidic solutions down a well to dissolve uranium and pump the mineral‑laden fluid back to the surface. This method has a tiny surface footprint and is cost‑efficient. By 2024 it accounted for more than half of global uranium production [1]. The geology is favourable too. Kazakhstan holds about 14 % of the world’s uranium resources and produced 23,270 tonnes U (tU) in 2024 [4].

Scale amplifies the geological edge. The state‑controlled miner Kazatomprom runs thirteen ISL projects, most in partnership with foreign firms. In 2024 it produced 12,463 tU, roughly one‑fifth of global output [1]. Partners include Canada’s Cameco at the Inkai deposit and France’s Orano at Moinkum. The company listed 15 % of its shares on the Astana and London exchanges in 2018, but the sovereign wealth fund Samruk‑Kazyna still owns 75 % [4]. That ownership allows the government to calibrate production levels like a national strategy.

Chemistry and logistics round out the picture. ISL mining relies on huge volumes of sulfuric acid, and Kazakhstan enjoys low‑cost domestic supplies. Yet the advantage is fragile. A shortage of sulfuric acid forced Kazatomprom to trim its 2025 production plans by 12–17 % [5]. Guidance for 2025 points to 25–26.5 k tU of output [5]. That would keep the country’s share near 40 % but underscores how sensitive the market is to bottlenecks on the Kazakh steppe.

Market leverage and supply concentration

With such dominance, Kazakhstan wields outsize influence. Together with Canada and Namibia, it produces about two‑thirds of the world’s natural uranium [1][7]. Most of this supply is sold under multi‑year contracts rather than volatile spot markets. These long deals give utilities assurance but also entrench the leverage of major producers [6]. When one supplier falters—as when Kazatomprom flagged acid shortages—prices spike and buyers scramble.

Demand is rising faster than new supply. Mine output met only 80–90 % of reactor requirements in 2024 [13]. The World Nuclear Association expects uranium demand to rise by 28 % by 2030 and more than double by 2040 [3]. At least 71 GWe of capacity is already under construction [3]. Programmes in Japan, South Korea, the United States and parts of Europe are reviving. Stockpiles are dwindling, and long‑term contracts cover most demand. As a result, the market depends heavily on a few producers to deliver.

Processing hubs, flows and reliance

The journey from mine to reactor involves conversion, enrichment and fuel fabrication. Here the bottlenecks are even tighter than in mining. France, China, Canada and Russia account for roughly 90 % of conversion capacity, while Russia and Europe control about 90 % of enrichment [7]. In 2023 just four companies supplied 97 % of uranium hexafluoride delivered to European utilities—Orano, Cameco, ConverDyn and Rosatom—and 37.9 % of the enriched product still came from Russia [7]. The World Nuclear Association’s table of enrichment capacity shows that Rosatom controls about 44 %, Urenco 29 %, China’s CNNC 14 %, and Orano 12 % [8]. Major refineries and converters include Orano’s Comurhex plant in France, Cameco’s Port Hope plant in Canada, the China National Nuclear Corporation’s facilities, and Russia’s Angarsk site.

Such concentration means that even countries that buy ore from trusted partners remain exposed midstream. In 2023, 77 % of the natural uranium delivered to European Union utilities came from Canada (31.9 %), Russia (23.8 %) and Kazakhstan (21.3 %) [7]. After conversion, much of this material heads to enrichment plants in Russia or to Europe’s Urenco consortium. France, the Netherlands, Germany and the United Kingdom operate their own enrichment facilities. Yet they still rely on Russian capacity for flexibility. The United States and Canada are developing new conversion and enrichment projects, but these will not change the balance until late this decade [8].

China is building its own supply chain. State‑owned firms hold stakes in all of Namibia’s producing mines, and Namibia sends 77 % of its uranium exports to China [9]. The Chinese also buy about 30 % of Kazakhstan’s exports [9] and invest in new mines in Brazil and elsewhere [9]. For Western utilities, this means that much of the “rest of the world” supply flows eastward.

Geopolitics: Russia’s war and Kazakh vulnerability

The energy transition’s quiet champion sits in a tricky geopolitical neighbourhood. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 shocked Kazakhstan and prompted it to distance itself diplomatically from Moscow. Kazakh leaders have reaffirmed the principle of territorial integrity and chosen neutrality at the United Nations [10]. Yet the economy remains entangled with its northern neighbour. About 80 % of Kazakhstan’s oil exports transit Russian pipelines, and the country relies on Russian imports for refined fuels and nuclear services [10]. Russian politicians have occasionally hinted that Kazakhstan could face a similar fate to Ukraine [10], reminding the region of its volatility.

For uranium, the risk is twofold. Transit is the first risk. Most of Kazakhstan’s concentrate travels by rail through Russia en route to conversion plants in Siberia or to ports bound for China and Europe. The second risk is midstream reliance. Kazakhstan lacks large‑scale conversion and enrichment facilities and must send ore to Russia or China before it can become fuel. A serious escalation of the Russia‑Ukraine conflict—such as sanctions blocking Russian transit or outright aggression against Kazakhstan—would be a black swan for the uranium market. Such a shock could disrupt half of the world’s supply at a stroke. The scenario is unlikely, but the war has already spurred Western utilities to seek alternative routes via the Caspian Sea or South‑East Asia and to stockpile more material.

Counterweights and emerging producers

Could other countries fill the gap? Canada has restarted its McArthur River and Cigar Lake mines and produced about 14,309 tU in 2024—roughly 23 % of world output [11]. Canada’s expansion plans are modest and depend on price signals. Namibia produced around 7.3 k tU in 2024, about 12 % of global supply [12], yet much of this output is contractually tied to Chinese buyers [9]. Australia holds 28 % of global uranium resources but mined just 4.6 k tU (≈ 7 % share) in 2024 [12]. Domestic politics and environmental concerns limit expansion there. Uzbekistan and Russia each supply roughly 5–7 %, while Niger contributes about 1.6 % [12]. Even combined, these producers cannot replace Kazakhstan. GlobalData forecasts that world mine output must grow by about 8 % annually to meet demand [11]. Most of that growth is expected to come from existing giants and new African projects.

So What?

The world is betting on a nuclear comeback to decarbonise electricity and power energy‑hungry industries. Yet the fuel chain behind it remains startlingly concentrated. About 40 % of mined uranium comes from Kazakhstan and around 44 % of enrichment capacity is located in Russia [3][8]. A disruption in either country would ripple across electricity markets. The war in Ukraine has already exposed Western reliance on Russian conversion and enrichment [10]. Tensions with China show how supply lines can be redirected eastward. Meanwhile, demand is poised to surge. The World Nuclear Association expects uranium requirements to jump 28 % by 2030 and more than double by 2040 [3].

For policymakers, the message is clear: treat the entire fuel cycle as strategic infrastructure. Diversifying mining beyond Kazakhstan and building conversion and enrichment capacity outside Russia and China are essential to ensure a stable supply. Transparent international partnerships are also necessary. Canada and the United States are planning new conversion and enrichment plants. The European Union is exploring alternative transit routes, and African nations are seeking investment. But these efforts will take years to bear fruit.

For investors, the focus should extend beyond spot prices. They should watch the health of sulphuric‑acid plants in the Kazakh steppe, the speed of centrifuge installations in North America, and the scale of Chinese offtake agreements in Namibia and Brazil. For readers, the key takeaway is simple: the nuclear renaissance rests on a delicate chain that crosses geopolitical fault lines. Geology and geopolitics, not just engineering, will determine whether the world’s reactors have enough fuel.

References

[1] World Nuclear Association. “World Uranium Mining Production” (23 Sept 2025). Available at: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/mining-of-uranium/world-uranium-mining-production

[2] GlobalData via Mining Technology. “PDAC 2025: Kazakh uranium miners look to take advantage of nuclear resurgence” (2 Mar 2025). Available at: https://www.mining-technology.com/features/pdac-2025-kazakh-uranium-miners

[3] Reuters. “Uranium demand set to surge 28 % by 2030 as nuclear power gains momentum, WNA says” (5 Sept 2025). Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/uranium-demand-set-surge-28-by-2030-nuclear-power-gains-momentum-wna-says-2025-09-05

[4] World Nuclear Association. “Uranium and Nuclear Power in Kazakhstan” (country profile). Available at: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/kazakhstan

[5] World Nuclear News. “Kazatomprom lowers 2025 uranium production expectations” (23 Aug 2024). Available at: https://world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Kazatomprom-lowers-2025-uranium-production-expectations

“Kazatomprom to lower uranium production in 2026” (22 Aug 2025). Available at: https://world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Kazatomprom-to-lower-uranium-production-in-2026

[6] U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Uranium Marketing Annual Report 2024” (2025). Available at: https://www.eia.gov/uranium/marketing

[7] Watt‑Logic. “The uranium fuel supplies are highly concentrated” (22 Jul 2024). Available at: https://watt-logic.com/2024/07/22/uranium-fuel-supplies-are-highly-concentrated

[8] World Nuclear Association. “Uranium Enrichment” (updated 6 Jun 2025). Available at: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/conversion-enrichment-and-fabrication/uranium-enrichment

[9] Center for Strategic & International Studies. “Fueling the Future: Recommendations for Strengthening U.S. Uranium Security” (2025). Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/fueling-future-recommendations-strengthening-us-uranium-security

[10] European Council on Foreign Relations. “Steppe change: How Russia’s war on Ukraine is reshaping Kazakhstan” (13 Apr 2023). Available at: https://ecfr.eu/publication/steppe-change-how-russias-war-on-ukraine-is-reshaping-kazakhstan

[11] GlobalData. “Global uranium production expected to grow modestly in 2025” (2025). Available at: https://www.mining-technology.com/data-insights/global-uranium-production-expected-to-grow-modestly-in-2025

[12] World Nuclear Association. “World Uranium Mining Production” (23 Sept 2025). Available at: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/mining-of-uranium/world-uranium-mining-production

[13] Investing News Network. “Uranium Price Update: Q2 2025 in Review” (29 Jul 2025). Available at: https://investingnews.com/uranium-price-update-q2-2025-in-review