China once powered global economic growth with its massive workforce and booming factories. Now, China’s population crisis threatens to upend that engine of expansion.

For decades, the country’s economic miracle relied on one key ingredient: people. Lots of them. Young workers flooded into cities, built products for the world, and drove unprecedented growth. But that demographic strength is now unraveling—and the consequences could reshape the global economy.

The Numbers of China’s Population Crisis Tell a Stark Story

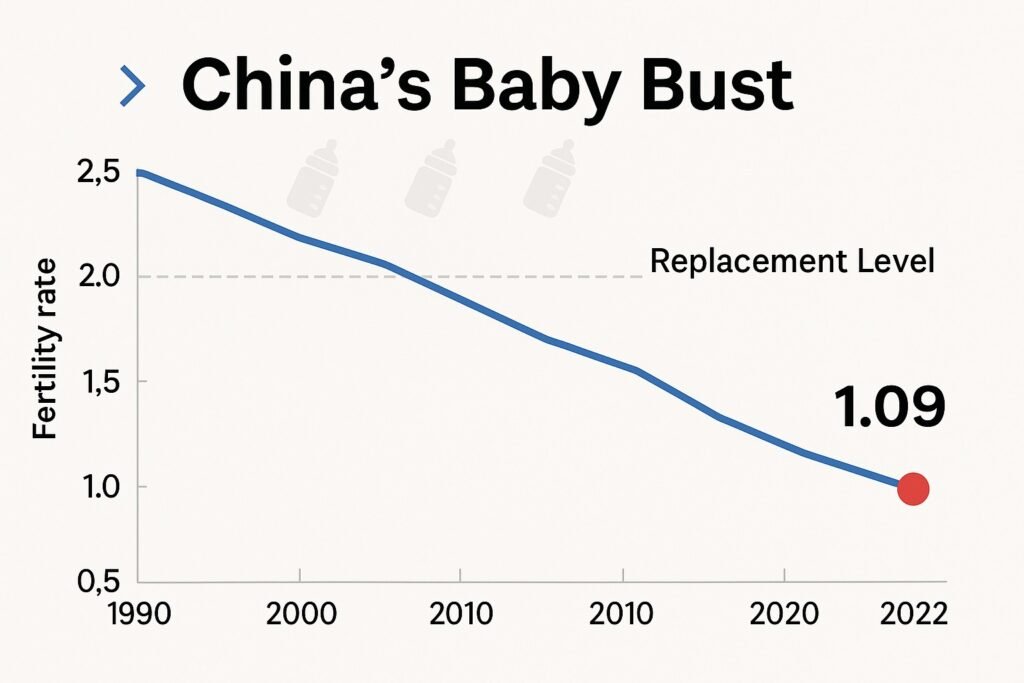

China’s population declined in 2022 for the first time since the 1960s. This isn’t just a blip—it signals the start of a long-term demographic collapse.

Here are the key figures that paint the picture:

- Birth rates are plummeting. China’s fertility rate hit just 1.09 children per woman in 2022. To maintain a stable population, countries need a fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman. China falls far short of this replacement rate.

- The population is shrinking. After peaking at 1.41 billion people in 2021, China’s population has started declining. Government projections suggest it could fall to 1.31 billion by 2050—a loss of 100 million people.

- The country is aging rapidly. China’s median age is 39 today. By 2050, it’s expected to surpass 50. Compare this to the United States, where the median age is 38 and rising much more slowly.

- Gender imbalances persist. By 2020, China had roughly 34 million more men than women. This “marriage squeeze” means millions of men cannot find partners, further reducing birth rates.

How China Created Its Own Demographic Disaster

The One-Child Policy Legacy

From 1979 to 2015, China enforced one of the world’s strictest family planning policies. The one-child policy aimed to control rapid population growth and boost economic development.

The policy worked too well. Chinese families, traditionally large, suddenly had only one child. This created what demographers call a “demographic dividend”—a large working-age population supporting fewer dependents. This dividend fueled China’s economic boom from the 1980s through 2000s.

But policies have consequences. The one-child policy also created deep cultural shifts. Traditional Chinese families valued sons over daughters, leading many families to prefer male children. This preference, combined with the one-child limit, resulted in significant gender imbalances.

Modern Pressures Keep Families Small

Even after China ended the one-child policy in 2015 and now allows three children per family, birth rates continue falling. Why?

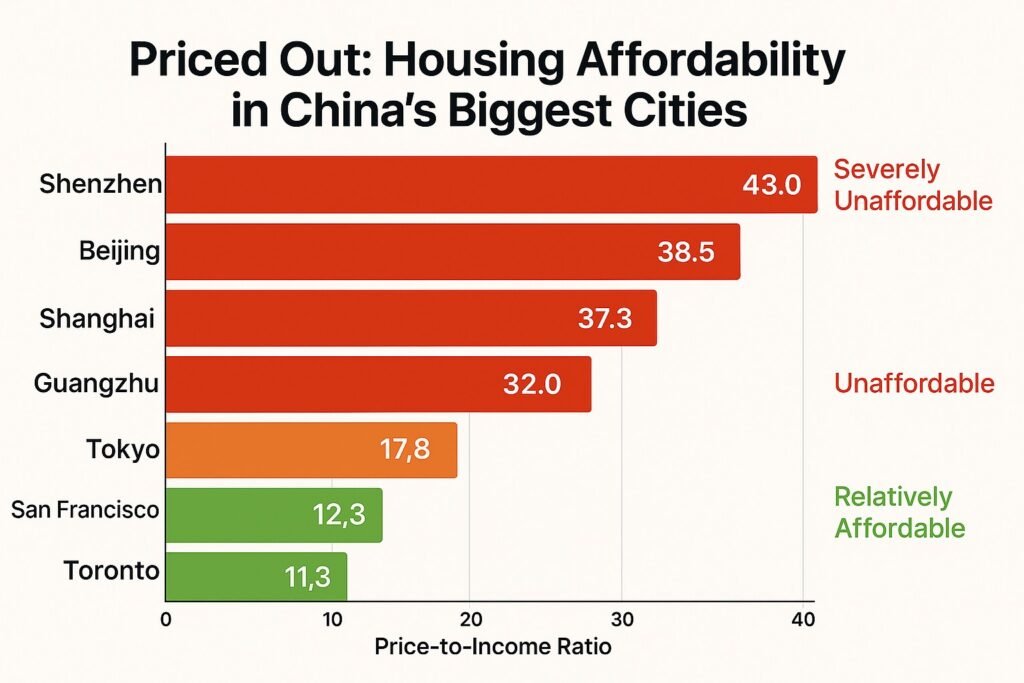

- Urban living costs are crushing young families. Housing prices in major Chinese cities rank among the world’s highest relative to income. A typical apartment in Beijing or Shanghai can cost 20-30 times the average annual salary. Young couples often cannot afford larger homes needed for children.

- Education competition is intense. Chinese parents face enormous pressure to provide the best education for their children. This includes expensive tutoring, extracurricular activities, and preparation for competitive university entrance exams. The financial and time commitment for one child is already overwhelming.

- Career priorities have shifted. China’s younger generation, especially women, increasingly prioritize career advancement over traditional family roles. Many delay marriage and childbearing, or choose to remain childless entirely.

- Cultural attitudes are changing. Surveys show that younger Chinese adults are less interested in marriage and children than previous generations. They value personal freedom, travel, and lifestyle choices over family obligations.

China’s Aging Population Creates Multiple Crises

The Labor Force Is Shrinking

China’s working-age population (ages 15-64) peaked in 2015 at about 1 billion people. Since then, it has declined by millions each year. By 2050, China could lose 200 million working-age people.

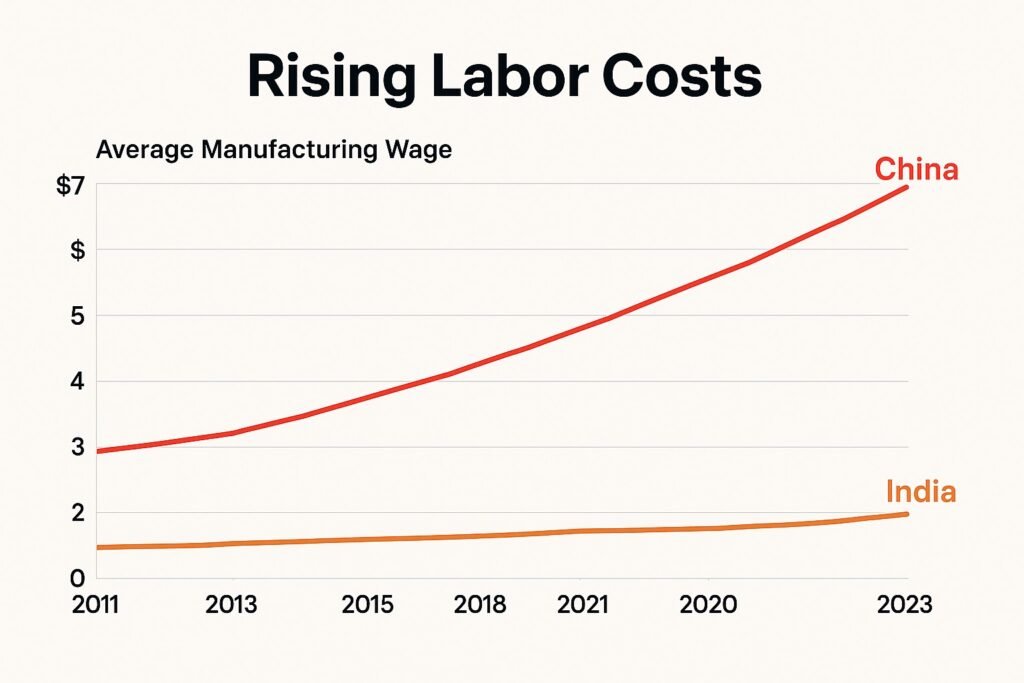

This labor shortage is already visible in Chinese factories. Manufacturing wages have risen 300% since 2005 as employers compete for fewer workers. Many factories now struggle to find enough employees, especially for physically demanding jobs.

Healthcare and Pension Costs Are Exploding

In 1980, only 5% of China’s population was over 65. Today, that figure is 14%. By 2050, it will exceed 30%—meaning nearly one in three Chinese people will be elderly.

This rapid aging creates enormous fiscal pressure. China’s pension system, already strained, must support far more retirees with fewer working-age contributors. Healthcare costs are also surging as older populations require more medical care.

The government estimates it will need to spend an additional $3 trillion on elderly care and pensions over the next decade. This massive spending requirement comes as economic growth slows, creating a dangerous fiscal squeeze.

Consumer Spending Is Weakening

Older populations spend differently than younger ones. Elderly people typically save more and spend less on consumer goods, travel, and entertainment. As China’s population ages, domestic consumption—a key driver of economic growth—is weakening.

This shift is already visible in China’s retail sector. Sales of cars, electronics, and luxury goods have slowed significantly. The country’s massive shopping malls, once packed with young consumers, now see declining foot traffic.

Global Economic Shockwaves

The End of Cheap Chinese Manufacturing

For decades, global companies relied on China’s vast supply of low-cost workers to manufacture everything from smartphones to furniture. This era is ending.

Rising wages and labor shortages are making Chinese manufacturing less competitive. Many companies are shifting production to countries with younger, cheaper workforces like Vietnam, Bangladesh, and India. This trend, called “nearshoring” or “friend-shoring,” accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic and continues today.

Reduced Global Demand

China isn’t just the world’s factory—it’s also a massive consumer market. Chinese tourists, students, and businesses have been major sources of global demand for decades.

As China’s economy slows and its population ages, this demand is weakening. Countries that export raw materials to China—like Australia (iron ore), Brazil (soybeans), and Chile (copper)—are seeing reduced orders. European luxury brands report declining sales as fewer Chinese consumers travel abroad.

Investment and Trade Implications

China’s population crisis affects global financial markets in several ways:

- Reduced foreign investment. International investors are becoming more cautious about long-term investments in China. Slower population growth means weaker domestic markets and reduced profit potential.

- Currency pressure. China may need to devalue its currency to maintain export competitiveness as labor costs rise. This could trigger global currency volatility.

- Supply chain restructuring. Companies worldwide are diversifying their supply chains away from China. This process, while necessary, is expensive and disruptive to global trade patterns.

Is China’s Population Crisis Solvable?

Government Efforts Fall Short

Chinese leaders recognize the severity of the demographic crisis. Since 2015, they have implemented numerous policies to encourage births:

- Family planning relaxation. The government ended the one-child policy and now allows three children per family. Some regions offer cash bonuses for second and third children.

- Financial incentives. Cities offer housing subsidies, tax breaks, and extended maternity leave to encourage childbearing. Some regions provide free childcare and education benefits.

- Cultural campaigns. The government promotes traditional family values and discourages “lying flat” (a youth movement rejecting traditional success pressures).

However, these efforts have had minimal impact. Birth rates continue declining despite government incentives. Many young Chinese say financial pressures and lifestyle preferences outweigh government benefits.

Technology and Automation as Solutions

China is betting heavily on technology to offset its shrinking workforce. The country leads global investment in industrial robots, artificial intelligence, and factory automation.

Chinese manufacturers are installing robots at record pace. The country now has more industrial robots than any other nation. Automated factories can operate with far fewer human workers, potentially offsetting labor shortages.

But technology has limits. Many service jobs—healthcare, education, eldercare—cannot be easily automated. As China’s elderly population grows, it will need more human workers in these sectors, not fewer.

[Insert Visual: Bar chart of global robot installations by country, highlighting China’s lead]

The Japan Comparison: Growing Old Before Getting Rich

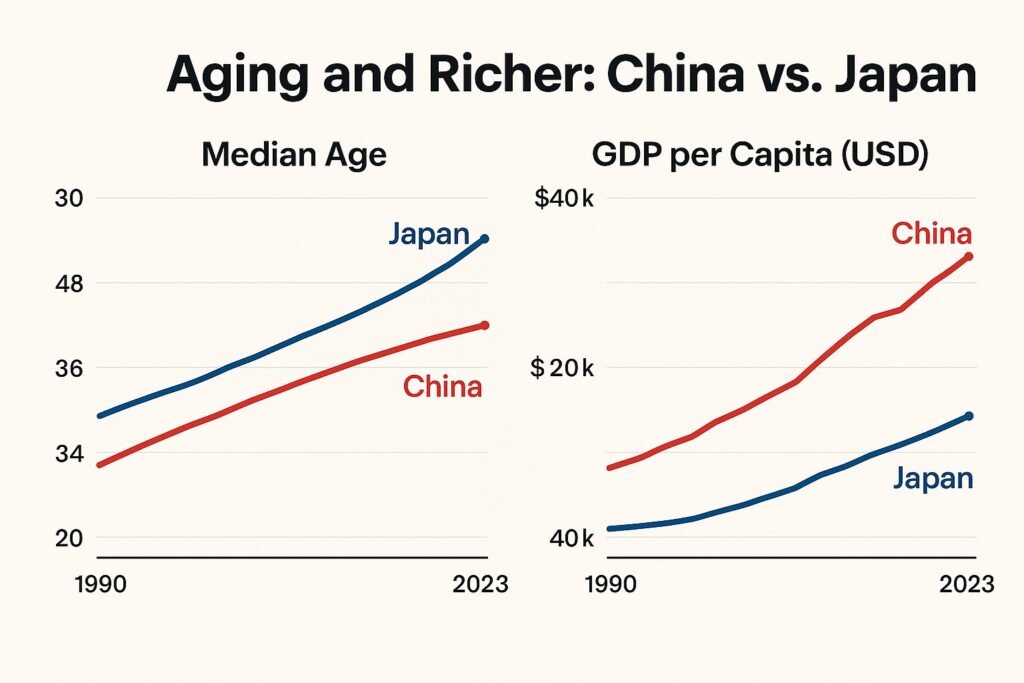

Japan faced a similar demographic crisis starting in the 1990s. However, Japan had a crucial advantage: it became wealthy before its population aged.

When Japan’s demographic transition began, its per capita income was already among the world’s highest. The country had mature institutions, advanced technology, and substantial savings to manage the transition.

China faces a harder path. Its per capita GDP of approximately $12,000 remains far below developed country levels. The country must manage demographic decline while still trying to escape middle-income status.

This creates what economists call the “middle-income trap.” Countries that grow old before growing rich often struggle to achieve high-income status. They lack the resources to support aging populations while investing in productivity growth.

What China’s Population Crisis Means for the Global Economy

A Multipolar World Order

China’s demographic decline accelerates the shift toward a multipolar global economy. No single country will dominate global growth the way China did from 2000-2020.

India, with its younger population and growing economy, is positioned to capture some of China’s role. Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and Indonesia also benefit from demographic advantages and increasing foreign investment.

The United States, despite its own aging population, maintains advantages in technology, higher education, and immigration that help offset demographic challenges.

Supply Chain Reshaping

Global supply chains, built around Chinese manufacturing, must adapt to new realities. This transformation will take decades and cost trillions of dollars.

Companies are developing “China+1” strategies—maintaining some Chinese operations while building alternative supply chains in other countries. This diversification reduces risk but increases complexity and costs.

Investment Opportunities and Risks

China’s demographic crisis creates both opportunities and risks for global investors:

- Opportunities exist in automation, healthcare, and eldercare sectors. Companies providing robots, medical equipment, and senior services may benefit from China’s aging population.

- Risks include reduced Chinese consumption and slower global growth. Traditional sectors serving Chinese consumers—luxury goods, tourism, commodities—may face permanent demand reduction.

The Road Ahead

China’s demographic crisis represents one of the most significant economic shifts of the 21st century. The country that powered global growth for four decades is now turning inward, focused on managing decline rather than driving expansion.

This transition affects everyone. Global supply chains must adapt. Investment patterns will shift. Economic growth may slow worldwide as the Chinese engine weakens.

For businesses, investors, and policymakers, the message is clear: the era of China as the world’s growth engine is ending. The future global economy will be more diverse, more complex, and potentially less dynamic.

Understanding these demographic forces is crucial for anyone planning for the next two decades. China’s population crisis isn’t just China’s problem—it’s reshaping the world economy in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

The question isn’t whether China’s demographic decline will affect the global economy. The question is how quickly we can adapt to this new reality.