The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths. That 1992 quote from Deng Xiaoping wasn’t marketing fluff—it was prophecy. Today, China’s rare earth dominance is showcased by the control of upwards of 85% of the world’s refined rare earth production, turning what should be a mundane mineral market into a geopolitical chokepoint [1]. But here’s the twist nobody talks about: China doesn’t necessarily sit on the world’s largest pile of rare earth ore. What China controls is far more valuable—the ability to turn raw rocks into the components that power modern life.

What Are Rare Earths, and Why They’re Everywhere

Despite their name, rare earth elements aren’t actually rare. Cerium is more common in Earth’s crust than copper [2]. However, these 17 metals—ranging from lanthanum to dysprosium—are typically scattered through ore in low concentrations, making extraction challenging, expensive, and environmentally damaging.

Here’s why they matter: rare earths are the vitamins of high-tech industry. They possess magnetic, luminescent, and electrochemical properties that have no easy substitutes. A neodymium-based magnet is small, powerful, and efficient. The alternatives? Bigger, heavier, weaker, or all three.

Take a Tesla Model 3. Inside its motor sits about 1–2 kg of rare earth magnets [3]. That magnet—crafted from neodymium and dysprosium—gives the car torque without bloating the engine. Multiply that across millions of EVs, and you’ve got a supply chain that can’t exist without these metals.

Military systems are even more demanding. Each U.S. F-35 fighter jet contains around 417 kg of rare earth material embedded in electric drive systems and stealth coatings [1]. A Virginia-class nuclear submarine? Nearly 4.2 tons [1]. Your iPhone uses at least eight rare earth elements—neodymium in the speaker, europium and terbium in the display, lanthanum in the camera lens [1]. Hard disk drives, catalytic converters, medical MRI machines, wind turbines—all depend on these metals.

The global rare earth market is valued at only $6–8 billion annually, a relatively small amount compared to oil or semiconductors.[2] But that low dollar value masks enormous strategic power. Control the supply, and you control whether the world can build EVs, wind farms, fighter jets, or smartphones.

How China Built a 30-Year Stranglehold

China’s rare earth dominance wasn’t geology. It was strategy.

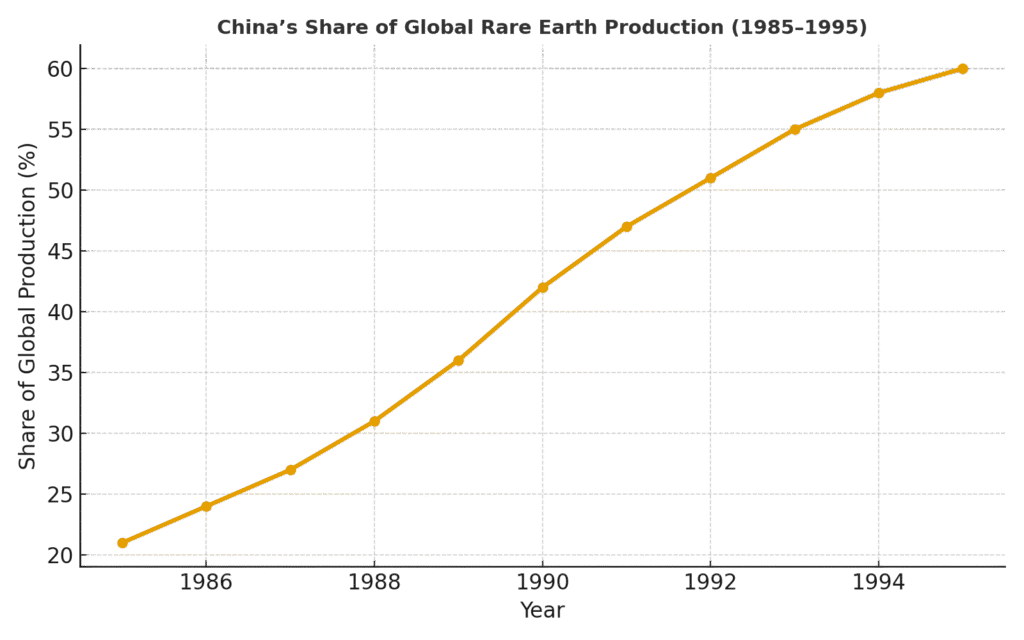

In the 1980s and 1990s, while the United States operated the world’s largest rare earth mine and Europe ran active refining hubs, Beijing made a calculated move: undercut everyone. The Chinese government introduced export tax rebates for rare earth producers, making Chinese materials absurdly cheap [1]. Labor was cheap. Environmental rules were lax. Between 1985 and 1995, Chinese output quintupled, rocketing from 21% to 60% of global production in a single decade [1].

By the early 1990s, China declared rare earths a protected strategic resource, barring foreign firms except through joint ventures—forcing Western companies to share technical know-how [1]. A pivotal moment came in 1997 when Chinese buyers acquired Magnequench, a U.S.-based GM subsidiary that pioneered neodymium magnet production. Soon after, manufacturing moved to China, erasing America’s lead in magnet technology [1].

China then tightened export quotas, discouraging raw ore sales and incentivizing processed materials and finished magnets. The message: buy value-added products from China, or better yet, manufacture here [1].

The strategy peaked in 2010. Frustrated by a maritime dispute with Japan, China cut its rare earth export quota by 37%, sending prices from roughly $9,500 per ton to $67,000 per ton in two years [1]. Western manufacturers faced scarcities. Chinese domestic users enjoyed an ample supply at a lower cost. China’s downstream industries—magnet makers, electronics firms—boomed [1].

By the 2010s’ end, China had captured stunning market share: roughly 85% of refined rare earth oxides and over 90% of metals, alloys, and permanent magnets [1]. In 2019, China accounted for 92% of global rare earth permanent magnets—critical for EVs, wind turbines, and weapons systems [1]. Even as new mines opened elsewhere, China held firm. It wasn’t just mining dominance; it was processing dominance.

The Real Power: Refining, Not Mining

Here’s where the story gets interesting—and where most people miss it.

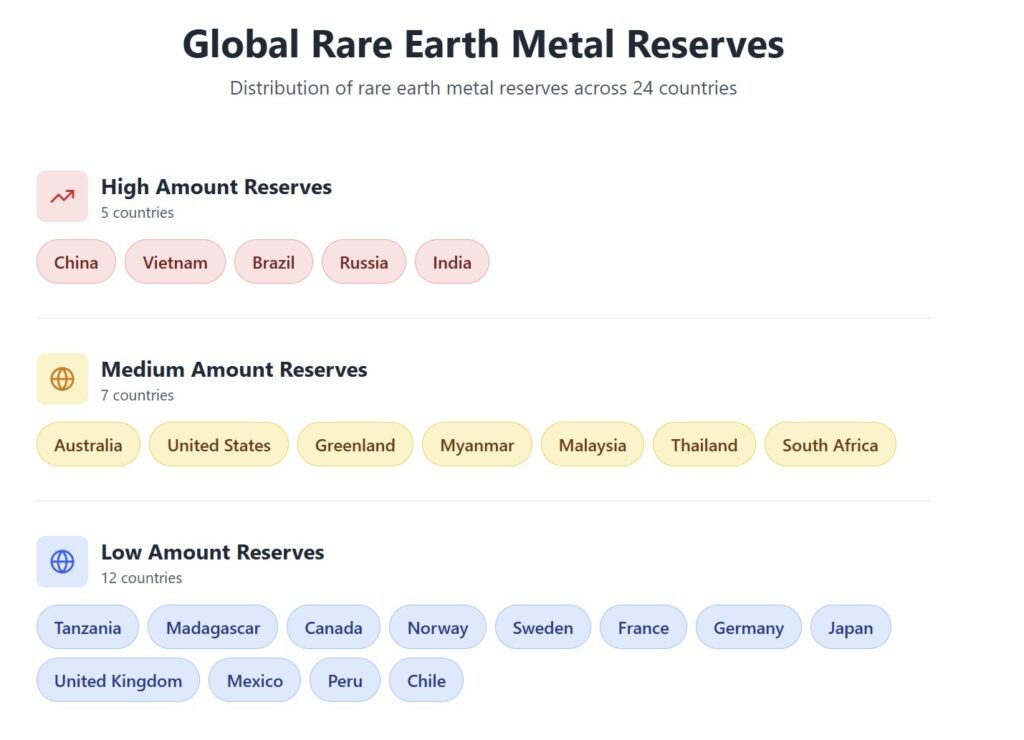

China doesn’t control the largest share of the world’s rare earth ore. The country holds roughly 36% of global reserves [1]. The United States sits on enough to meet global demand for decades. Significant deposits exist in Vietnam, Brazil, Australia, and India [4].

But having reserves is useless without processing capacity. And here, China is virtually unrivaled.

America’s Mountain Pass mine, reopened in 2018, initially sent 100% of its rare earth concentrate to China for separation and refining—because no facility elsewhere could do it economically [1]. Australia’s Lynas Corporation, the world’s largest non-Chinese producer, mines ore in Australia but ships it to Malaysia for processing; China had driven out competitors decades earlier [1].

For heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium—elements that give magnets their heat resistance for EV motors and jet engines—China’s grip is absolute. Nearly 100% of the world’s separated heavy rare earth oxides come from Chinese refineries [2]. China even imports raw feedstock from abroad and processes it for export, maintaining control over the entire value chain.

Myanmar illustrates this perfectly. Over the past decade, Myanmar emerged as a major source of heavy rare earth ore. By 2022–2023, Myanmar was supplying roughly 70% of China’s feedstock for medium-to-heavy rare earths like dysprosium [5]. Chinese companies extract ore-rich clays, truck them into Yunnan province, and refine them in massive facilities [5].

The point: China doesn’t need to monopolize all raw ore. By controlling refining capacity, it can source materials globally, add value domestically, and pocket the profit. Other countries dig. China processes and profits.

This is reinforced by expertise. China has spent three decades building know-how. The country churns out hundreds of trained separation engineers annually, while the U.S. has had virtually none for years [4]. Baotou and Changchun are global rare earth innovation hubs, bristling with R&D centers and patents [4].

The Defense and Clean Energy Paradox

The U.S. Department of Defense estimates that every $1 million of defense output contains $5–10 worth of rare earths [1]. Precision-guided munitions use neodymium magnets in control fins. Satellite communications rely on yttrium and gadolinium. Night-vision goggles depend on europium. As one former Navy admiral put it, “remove rare earths from U.S. defense, and our planes don’t fly and our ships don’t sail.”[1].

Here’s the irony: to transition away from fossil fuels, the world needs massive quantities of rare earth magnets for wind turbines and EV motors. Yet that transition depends on supply chains controlled by a geopolitical rival. The EU’s wind industry is heavily reliant on Chinese rare earth magnets for turbine generators [2].

If rare earth supply tightens, disruptions cascade into multiple sectors. A shortage of dysprosium doesn’t just affect mining; it means fewer EVs, drones, and wind turbines rolling off assembly lines.

The West Fights Back

For over a decade, policymakers have warned about China’s rare earth dominance. Real countermeasures are now underway across four fronts.

New mines: Mountain Pass in California now produces about 45,000 tons of rare earth ore concentrate annually, making the U.S. the world’s #2 producer [5]. Lynas in Australia produces 15,000–20,000 tons per year. Projects are underway in Canada, Australia, Africa, and even Greenland (though development has stalled due to environmental concerns) [4].

Processing capacity: Governments are subsidizing new separation plants. The Pentagon awarded contracts to Lynas and MP Materials to build domestic facilities. Lynas received funding for a heavy rare earth separation plant in Texas; if successful, it will handle Australian concentrates without sending them to China [1]. France’s Solvay announced plans to restart refining rare earth oxides. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act targets establishing at least 40% of EU refining domestically by 2030 [2].

Allied networks: Countries are building “friend-shored” rare earth supply chains. Japan invested $250 million in Lynas to secure non-Chinese supply after the 2010 export scare [1]. Lynas now supplies about 30% of Japan’s rare earth imports [1] By 2018, Japan had cut China’s share from 91% to 58%.[1] Yet for sensitive products like magnet alloys, Western reliance on China remains near-total at 95–99%.[1]

Recycling and alternatives: The West is investing in recycling infrastructure to recover rare earths from end-of-life electronics. Tesla announced plans to develop rare-earth-free EV motors [3]. As of today, roughly 80% of EV models still rely on rare-earth magnets, but alternatives are emerging [3].

Progress is real but slow. By 2019, China’s share of global rare earth mining had dropped to roughly 63%, the lowest since the mid-1990s [1]. Yet China still controls processing. A major risk looms: China can crash prices to bankrupt new competitors. After 2010’s spike, ventures like Molycorp collapsed when prices fell. Western startups today rely on government support [1].

The Trade War Accelerates

In August 2023, China slapped strict export licenses on gallium and germanium, two metals vital for semiconductors and military night vision, citing national security [6]. Exports to the U.S. and allies plummeted to near-zero [6].

By late 2025, China expanded restrictions to rare earth elements and magnet technology, targeting defense and chip industries [7]. Beijing required special licenses on exporting strategic heavy rare earths like dysprosium, or high-grade magnets destined for F-35s. China also announced that foreign companies using Chinese rare earth materials must get approval to re-export—an extraterritorial control mimicking U.S. chip regulations. Beijing signaled it would deny licenses for overseas military end-uses of rare earths [7].

In response, Trump announced a blanket 100% tariff on all Chinese goods, effective November 1, 2025, claiming retaliation for China’s export curbs [8]. This would double the cost of Chinese imports—unprecedented since Trump’s first term saw 10–25% tariffs.

The problem: tariffs alone are crude. During Trump’s first term, his administration considered tariffs on Chinese rare earths but backed down, precisely because there were no alternative suppliers for critical needs [1]. U.S. industry warned that tariffing Chinese rare earths would hurt American manufacturers without harming China, since Beijing could still sell to others [1].

But China’s export restrictions are more surgical and arguably more devastating. If China outright bans rare earth magnet exports, Western industries can’t instantly replace them. It would take years to scale non-Chinese magnet production. In the interim, carmakers and wind turbine manufacturers would face acute shortages. Prices would skyrocket globally (as they did in 2010 when China cut exports by just 37%). Companies might have to redesign products or delay product lines.

In essence, China’s rare earth dominance card is one of its strongest trump cards in any trade war.

Looking Ahead

By 2030, the world might split into parallel rare earth supply networks: one dominated by China, another serving the U.S., EU, Japan, and partners. China’s production share may shrink as new mines scale up, though the country will likely remain the largest player [7]. But the broader market could become less efficient and more politicized.

What was once an obscure mining niche is now recognized as a strategic lever. Nations will treat it as such. Rare earths won’t be the last critical material tug-of-war; cobalt, lithium, and others are on similar trajectories.

The bottom line: the world’s economic future can hinge on obscure inputs, and ignoring that fact is no longer an option.

References

[1] ChinaPower/CSIS, “Does China pose a threat to global rare earth supply chains?” (2021) – https://chinapower.csis.org/china-rare-earths/

[2] Polytechnique Insights, “China has a monopoly on rare earth metals” (January 2025) – https://www.polytechnique-insights.com/en/columns/geopolitics/china-has-a-monopoly-on-rare-earths/

[3] Reuters, “Tesla hits the brakes but rare earths juggernaut rolls on” (March 2023) – https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/tesla-hits-brakes-rare-earths-juggernaut-rolls-2023-03-08/

[4] National Defense Magazine, “China Maintains Dominance in Rare Earth Production” (September 2021) – https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2021/9/8/china-maintains-dominance-in-rare-earth-production

[5] Investing News Network, “Top 10 Countries by Rare Earth Metal Production” (2024) – https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/critical-metals-investing/rare-earth-investing/rare-earth-metal-production/

[6] Reuters, “China export curbs choke off shipments of gallium, germanium for second month” (October 2023) – https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-export-curbs-choke-off-shipments-gallium-germanium-second-month-2023-10-20/

[7] Reuters, “China expands rare earths restrictions, targets defense and chips users” (October 2025) – https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-tightens-rare-earth-export-controls-2025-10-09/

[8] Economic Times, “US doubles down on China with additional 100% tariff, effective November 1, 2025 or earlier” (October 2025) – https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/global-trends/trump-announces-100-tariffs-on-china-over-and-above-any-tariff-they-are-currently-paying/articleshow/124468423.cms?from=mdr