Almost overnight, one country has grabbed the steering wheel of a global supply chain worth tens of billions of dollars. Indonesia, an archipelago better known for beaches and palm oil, now mines more than half of the world’s nickel [1] and controls an even greater share of refined nickel used in stainless steel and electric-vehicle (EV) batteries [2]. In 2024, Indonesia produced 2.2 million tonnes of nickel out of a global total of 3.7 million, giving it a 59% market share [1]. The government’s bold mix of resource nationalism and industrial policy has turned the country from a commodity backwater into the choke-point of a metal that sits at the heart of clean-energy ambitions.

In this Minted Moves deep dive, we unpack how Indonesia captured the nickel crown, who stands to benefit (and who doesn’t), and why the world’s pivot away from oil may hinge on a string of smelters. Simply put, nickel is the new oil — and Jakarta knows it.

From Ore to Empire: The Numbers Behind Indonesia’s Nickel Boom

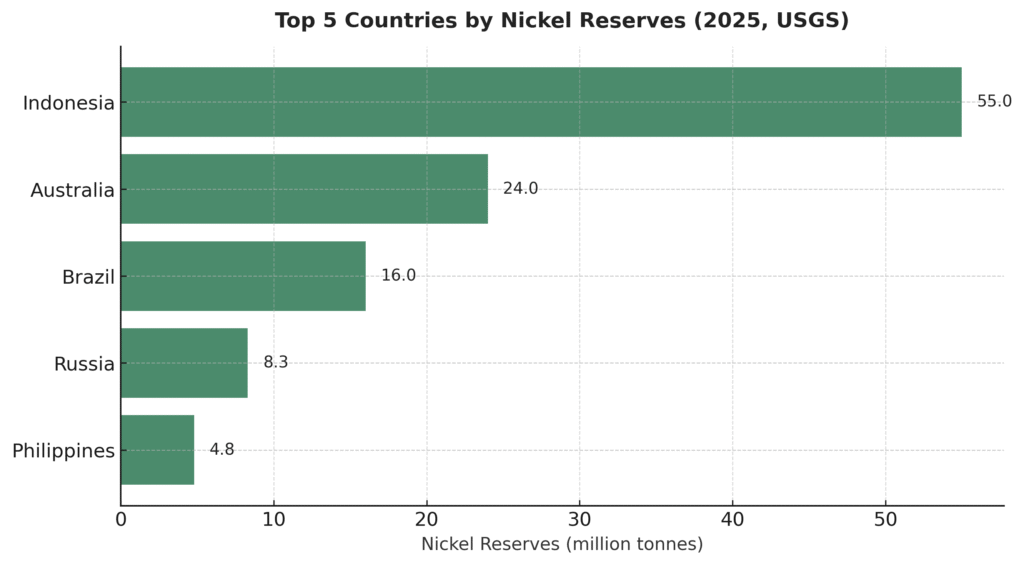

Nickel was once a niche commodity. Today, however, it’s essential for stainless steel (about 65% of demand) and for lithium-ion batteries (around 16%) used in EVs [1]. Historically, the market was fragmented: countries like Russia, Canada, Australia, and the Philippines each supplied meaningful shares.

That landscape changed dramatically after Indonesia’s 2014 ore-export ban (tightened in 2020), which forced foreign miners to build processing plants locally. The goal, however, wasn’t to reduce mining but to capture more value at home. Since smelters required a steady feed of ore, investors consequently poured billions into new mines to supply them. In other words, Jakarta’s export ban redirected rather than reduced production — transforming raw-ore exports into a domestic processing boom.

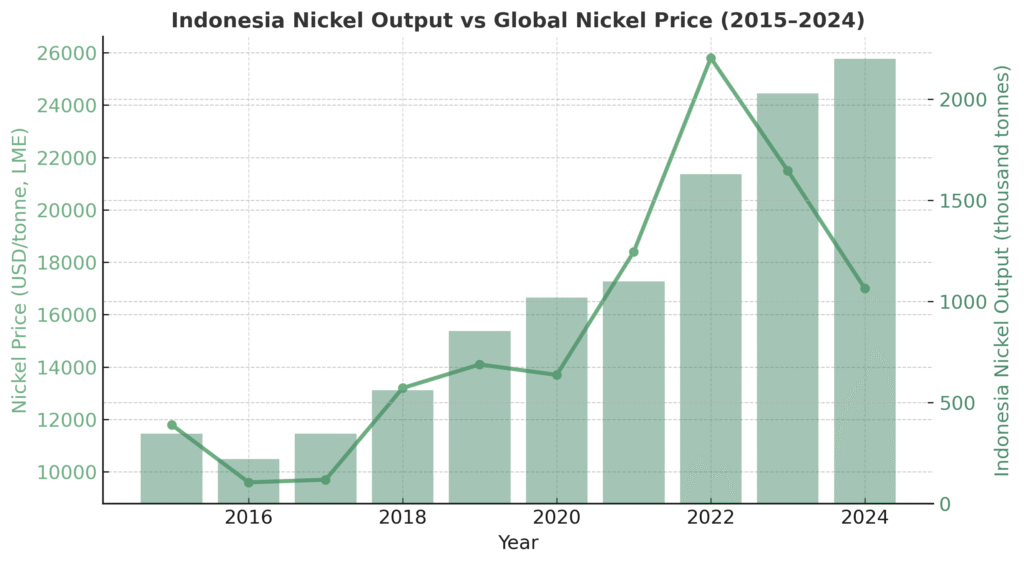

As a result, production exploded. In 2019, the country mined 853,000 tonnes of nickel; by 2024, output had jumped to 2.2 million tonnes — a 158% increase [3]. The U.S. Geological Survey, therefore, calls this surge the single largest driver of global supply growth [1]. Moreover, according to the IEA’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025, Indonesia produced over 60 % of the world’s mined nickel in 2024 [2], up sixteen-fold since 2015 [2]. Furthermore, the same report projects nickel output to climb another 25% by 2030, reaching 3 million tonnes and cementing its dominance [2].

Industrial policy has been equally decisive. The export bans created a captive market for smelting and refining, thereby attracting tens of billions in foreign investment. Consequently, Indonesia now hosts over 60 smelters — up from just two in 2016 [4]. Therefore, downstream exports were worth US $38–40 billion in 2024, up from US $11.9 billion in 2020 [4]. These include nickel pig iron, ferronickel, and the mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP) used in EV cathodes.

The China Factor: Financing, Processing, and Control

Indonesia’s nickel miracle has a silent partner: China. After Jakarta’s export ban, Chinese firms rushed in to finance processing plants. The Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) on Sulawesi and the Weda Bay Industrial Park on Halmahera are joint ventures between China’s Tsingshan Holding Group and Indonesian partners [5]. Transparency International reports that Chinese entities now control roughly 75 % of Indonesia’s nickel-smelting capacity and take 98 % of its nickel exports [6]. Investment has not slowed down; state-backed Chinese companies have pledged over US $30 billion to additional projects [5].

But this story isn’t just about EV batteries.

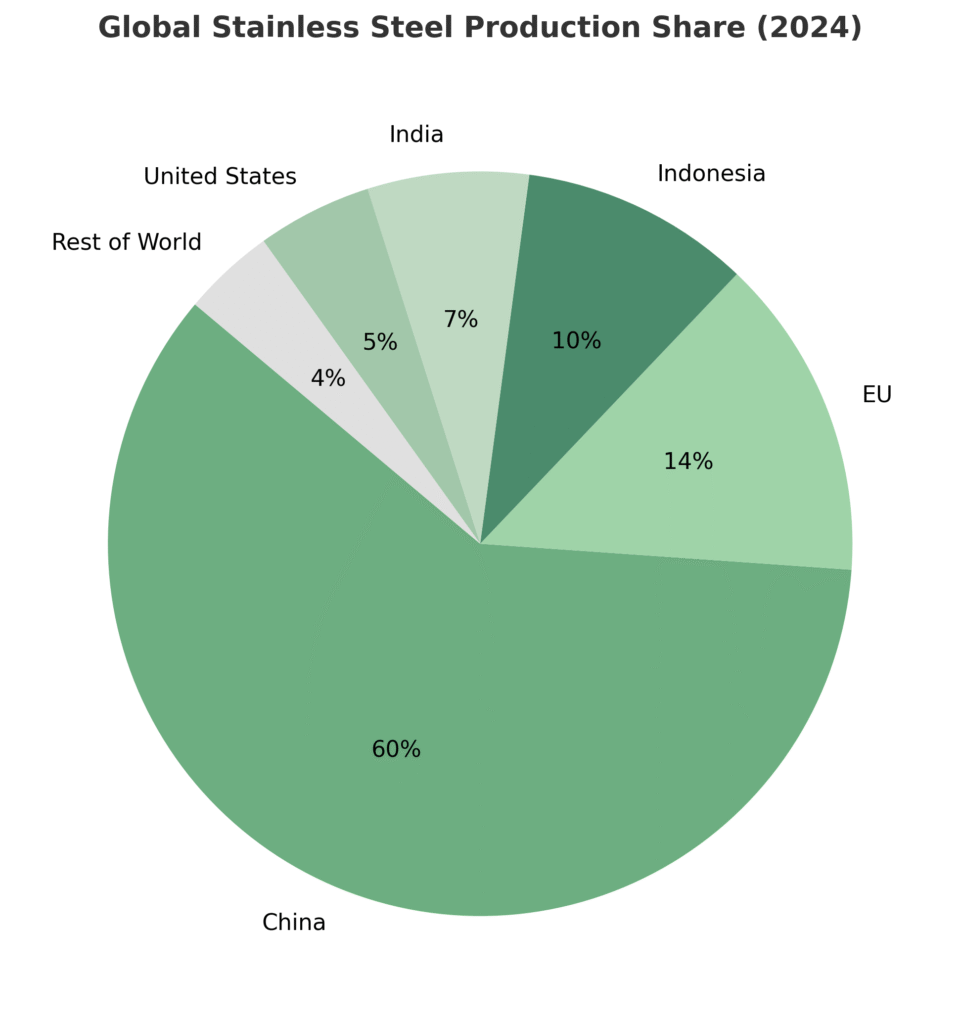

Roughly two-thirds of the world’s nickel still goes into stainless steel, and China dominates that market too — producing nearly 60 % of global output. Tsingshan, the same conglomerate leading Indonesia’s smelter boom, is also the world’s largest stainless-steel producer. By building smelters inside Indonesia, Chinese companies ensured a seamless supply of cheap nickel pig iron (NPI) to feed their steel mills, both in China and within Indonesian industrial parks themselves.

In effect, China has created a vertically integrated nickel empire:

Indonesia mines the ore, Chinese-financed smelters refine it, and Chinese steel and battery plants consume it. This system guarantees Beijing control over the materials of today’s infrastructure — stainless steel for buildings, pipelines, and appliances — and the technologies of tomorrow’s economy — batteries for EVs.

According to the IEA, the nickel market is becoming ever more concentrated, with the top country’s share rising sharply [2]. By 2040, Indonesia could account for 75 % of mined nickel [2]. Therefore, any policy shift in Jakarta or Beijing — from export quotas to green-energy rules — can send ripples through both the steel industry and EV supply chains worldwide.

Winners, Losers, and Geopolitical Fallout

Indonesia’s rise is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it has accelerated industrialisation, created tens of thousands of jobs, and boosted tax revenues. Domestic champions like Harita Nickel, Vale Indonesia, and Antam have expanded rapidly. Meanwhile, a Ford-led consortium invested US $3.8 billion in a new HPAL plant to secure 120,000 tonnes of MHP per year [7]. Furthermore, Jakarta is leveraging its minerals to negotiate EV assembly deals and build a domestic car industry.

Yet this dominance brings risk. In 2024, Nasdaq projected Indonesia’s share of global output to hit 63.4 % in 2025 [8]. However, oversupply has already crashed nickel prices — falling two-thirds between early 2022 and mid-2025 [9]. This price drop is squeezing miners in Canada, Australia, and New Caledonia; many have idled mines or sold assets. Reuters analysts warn the glut may last until 2028 [9]. Meanwhile, Indonesia plans to cut mining quotas by nearly 40% to prop up prices [10]. Such moves could reduce global supply by over a third and illustrate its OPEC-like power.

Why prices fell despite strong Chinese demand:

Even though China buys about 98% of Indonesia’s nickel, the global market still prices nickel through international benchmarks. When Indonesia flooded the system with cheap supply, total world inventories ballooned — and benchmark prices collapsed everywhere. In other words, the nickel found a buyer, but at a much lower price.

Winners vs Losers: For now, Chinese processors and EV makers benefit from cheap inputs. Indonesia collects taxes and builds infrastructure. Conversely, Western mines and EU policymakers face supply shocks and closures. India and the Philippines are trying to compete — but lack Indonesia’s resource depth.

Environmental and Labour Pressures

Indonesia’s nickel boom comes with steep environmental and social costs. Smelting hubs like IMIP and Weda Bay run on captive coal-fired plants that make up 12 % of Indonesia’s coal capacity [11]. Consequently, the sector is locking in high carbon emissions. An IEEFA study found that just four nickel companies could emit 39 million tonnes of CO₂ annually by 2028 [12]. In addition, deforestation and polluted waterways threaten biodiversity, while mining permits in Raja Ampat were revoked in 2025 after public protests [13].

Labour conditions raise similar concerns. Around 30 000 Chinese migrant workers live in crowded dormitories and endure 12-hour shifts. Local labour often earns less with weaker protections. Therefore, Indonesia’s industrial ambition also comes with a human cost that could ignite backlash both domestically and abroad.

So What? Nickel’s Global Leverage

Nickel may be a humble metal, but it is central to two megatrends: decarbonisation and geopolitical realignment. EV batteries still depend on nickel-rich chemistries for range, and although LFP batteries are gaining ground, the IEA expects nickel demand to double by 2040 to 5.5 million tonnes [14]. China consumes about 60 % of that today [15]; its battery-related nickel use could rise from 200 kt to 1.3 Mt by 2040 [16]. Yet, Indonesia — not China — controls the raw supply. Thus, Jakarta’s policies can sway the global energy transition.

High prices may invite new projects in Canada and Africa, but they take years to build and must compete with Indonesia’s scale. Consequently, the world faces price volatility: oversupply when Indonesian smelters run full tilt, and spikes whenever exports tighten.

For policymakers, diversification is urgent. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act rewards EVs built with non-Chinese, non-Indonesian minerals. However, recycling covers just 2 % of nickel demand [2]. Canada, Australia and the EU are offering tax breaks and “strategic project” status, yet replicating Indonesia’s resource base will be challenging.

Ultimately, Indonesia’s nickel strategy proves that a middle-income nation can rewrite global supply chains through resource leverage. Whether it acts as a steady supplier or a swing producer à la OPEC will shape the future of EVs and stainless steel for decades.

References

[1] United States Geological Survey. “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025 – Nickel.” (2025). Available at: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025-nickel.pdf

[2] International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025. (2025). Available at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ef5e9b70-3374-4caa-ba9d-19c72253bfc4/GlobalCriticalMineralsOutlook2025.pdf

[3] Mine Magazine. “Indonesia’s Nickel Market Stranglehold Tightens – Again.” Mine | Issue 151 (April 2025). Available at: https://mine.nridigital.com/mine_apr25/indonesia-nickel-market-2025

[4] Indonesian Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs and Investment. “Downstream Nickel Industrial Development Report 2024.” (2024). Available at: https://maritim.go.id/downstream-nickel-report-2024

[5] Tsingshan Holding Group and Weda Bay Industrial Park. “Investment and Operations Overview of Indonesia’s Nickel Industrial Parks.” (2024). Available at: https://wedabay.co.id/investment-overview-2024

[6] Transparency International Australia. Indonesia Case Study – Nickel Sector Governance and Investment Risks. (October 2025). Available at: https://mining.transparency.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/TIA_Indonesia_Case_Study_202510_ENG.pdf

[7] Investing News Network (INN). “Top 9 Nickel-Producing Countries.” (2025). Available at: https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/base-metals-investing/nickel-investing/top-nickel-producing-countries/

[8] Nasdaq. “Nickel Price Update: Q2 2025 in Review.” (2025). Available at: https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/nickel-price-update-q2-2025-review

[9] Reuters. “Nickel Oversupply to Persist on Expansion, Slower Demand Growth, Industry Experts Say.” (5 June 2025). Available at: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/nickel-oversupply-persist-expansion-slower-demand-growth-industry-experts-say-2025-06-05/

[10] Carbon Credits. “Nickel Prices at the Crossroads in 2025: Indonesia’s 40 % Production Cut Plan and EV Market Shifts.” (2025). Available at: https://carboncredits.com/nickel-prices-at-the-crossroads-in-2025-indonesias-40-production-cut-plan-and-ev-market-shifts-aemc/

[11] Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). “Indonesia’s Nickel Smelters and Coal Dependency.” (2024). Available at: https://ieefa.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/IEEFA%20Report%20-%20Indonesia’s%20nickel%20companies%20need%20RE_Oct2024.pdf

[12] IEEFA. Report – Indonesia’s Nickel Companies Need Renewable Energy Now. (October 2024). Available at: https://ieefa.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/IEEFA%20Report%20-%20Indonesia’s%20nickel%20companies%20need%20RE_Oct2024.pdf

[13] Reuters. “Indonesia Revokes Nickel Ore Mining Permits in Raja Ampat after Protest.” (10 June 2025). Available at: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/indonesia-revokes-nickel-ore-mining-permits-raja-ampat-after-protest-2025-06-10/

[14] International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 – Nickel Demand Forecasts. (2025). Available at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ef5e9b70-3374-4caa-ba9d-19c72253bfc4/GlobalCriticalMineralsOutlook2025.pdf

[15] IEA. “World Nickel Consumption by Region 2025.” (2025). Available at: https://iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2025

[16] IEA. “Projected Battery-Related Nickel Demand to 2040.” (2025). Available at: https://iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2025