Your morning coffee, the gas in your tank, even the wood in your house—Canada touches more of American life than most people realize. For starters, Canada is America’s second-largest trading partner (measured in total traded volume). Now, President Trump’s threat of a 100% tariff on all Canadian goods could turn that quiet economic partnership into a very loud wake-up call for U.S. consumers.

In January 2026, Trump floated the idea of slapping a 100% import duty on Canadian products, tying the threat to concerns about Canada’s potential trade deal with China[1]. Translation: if you import a $100 item from Canada, you’d now pay an additional $100 tax at the border. It’s not a tweak—it’s effectively doubling the cost of doing business with one of America’s largest trading partner.

Here’s what that actually means for the stuff you buy, the prices you pay, and why understanding U.S. Canada tariffs matters more than you think.

The Tariff Toolbox: How Washington Can Flip the Switch

Before diving into what gets more expensive, it helps to understand how tariffs actually work—and who really pays them.

A tariff is a tax on imports, paid by U.S. companies when goods cross the border[3]. Despite political rhetoric about “foreign countries paying,” American importers write the check to U.S. Customs[3]. Those companies then decide: absorb the cost (shrinking profits), raise prices (hitting consumers), or scramble for alternatives (disrupting supply chains).

The President can’t just tweet tariffs into existence. The Constitution grants Congress the power to levy tariffs, but over time Congress has delegated limited tariff authorities to the Executive through specific legislation[3]. He needs legal authority, typically invoking one of these tools:

National emergencies allow the fastest action. Using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), Trump imposed 35% tariffs on most Canadian imports in 2025 within days of declaring a border emergency[2]. The playbook for 100%? Likely the same rapid-fire approach.

National security exceptions offer another path. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act lets the President tariff imports deemed security threats[3]. In 2025, this justified 50% duties on Canadian steel and aluminum, plus 25% on autos[2]. Stretching “security” to cover nearly all Canadian goods would be legally creative, but not impossible.

Unfair trade practice provisions (Section 301) target specific violations, though they require investigation time[3]. The faster routes—emergency powers and security claims—are more probable for a sweeping 100% move.

The catch? Congress can push back, courts can challenge overreach, and trade agreements like USMCA create legal friction[3]. But none of these roadblocks are immediate. If the President pulls the trigger, the U.S. Canada tariffs hit first. The legal battles come later.

U.S and Canada Trade Through USMCA and The Current Tariff Reality

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) replaced NAFTA in 2020 with a promise: nearly tariff-free trade between the three countries. Over 99% of tariff lines between the U.S. and Canada were supposed to be zero[8]. Products that meet “rules of origin”—meaning they have sufficient North American content—enter duty-free.

For automobiles, that means at least 75% North American content by value[8]. For most other goods, the threshold varies, but the principle holds: make it in North America, pay no tariff.

In practice, though, U.S. Canada tariffs already exist despite USMCA. The agreement contains exceptions that the U.S. has repeatedly invoked:

Trade remedy duties override the free trade agreement entirely. Canadian softwood lumber currently faces combined antidumping and countervailing duties of roughly 14%[2], despite USMCA’s zero-tariff promise. The U.S. claims Canada subsidizes its lumber industry through low stumpage fees—the cost of harvesting timber from public lands.

Section 232 national security tariffs also bypass USMCA protections. As of 2025, Canadian steel and aluminum face 50% tariffs, timber products face 10-25% tariffs, and autos face 25% tariffs (though USMCA-compliant vehicles can claim exemptions)[2]. The U.S. argues these protect industries vital to national defense.

Emergency tariffs under IEEPA added another layer in 2025—35% on most Canadian imports that don’t meet USMCA rules of origin[2]. These target goods the administration claims are “transshipped” through Canada to avoid U.S. tariffs on China.

The bottom line: USMCA provides tariff-free access only when all sides honor it. National security exceptions, trade remedies, and emergency powers create gaping holes in that protection. By late 2025, roughly 11% of U.S. imports from Canada by value faced additional duties beyond the USMCA rate[2]. A 100% tariff would essentially nullify USMCA’s benefits altogether, either through legal exception or brute force.

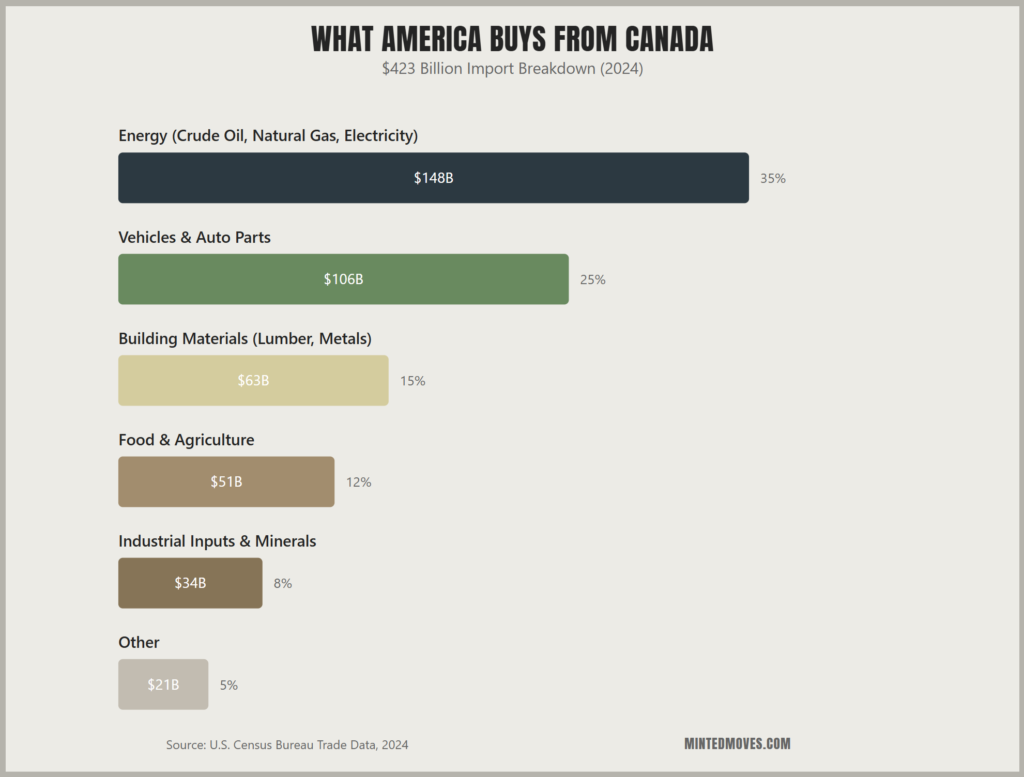

What America Actually Buys from Canada: The $423 Billion Supply Chain

Canada isn’t just maple syrup and hockey sticks. It’s helps to power the foundation of everyday American life, supplying everything from the fuel that powers your commute to the frame of your house.

In 2024, the U.S. imported roughly $423 billion worth of Canadian goods[2], making Canada the third-largest source of U.S. imports after China. That figure represents deeply integrated supply chains built over decades, where components and commodities cross the border multiple times during production.

Energy: The Lifeblood of American Transportation

Crude oil dominates the import relationship. About 60% of U.S. crude oil imports—roughly 4 million barrels per day (or ~20% of total U.S. petroleum consumption (in b/d terms))—flow from Canada[5]. That Canadian crude feeds refineries concentrated in the Midwest (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois) and Rocky Mountain states (Montana, Wyoming), producing the gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel that power American transportation[5].

Canadian oil isn’t easily replaceable. U.S. refineries, particularly in the Midwest, are configured to process heavy crude grades that Canada supplies. Switching to lighter domestic shale oil or importing heavy grades from Venezuela (sanctions complicate this) or the Middle East (higher transport costs) would require refinery retooling and months of adjustment[5].

Natural gas heats American homes. Northern states import Canadian natural gas via pipeline, with some regions heavily dependent on these flows for winter heating[5]. Any U.S. Canada tariff on energy would directly hit utility bills.

Electricity keeps lights on in New England and the Upper Midwest, where Canadian hydroelectric power supplements local generation[2]. Quebec’s vast hydro resources flow south through transmission lines, providing clean baseload power that would be expensive to replace quickly.

Vehicles and Auto Parts: The Integrated Assembly Line

One in four vehicles sold in America comes from Canada or Mexico[7], with Canadian plants producing popular models from GM, Ford, Chrysler, Toyota, and Honda. In Ontario alone, assembly plants churn out SUVs, pickup trucks, and sedans that fill American dealerships.

But the real story is in the parts. The North American auto industry operates as one integrated production system, with components crossing the U.S.-Canada border up to eight times during manufacturing[7]. An engine block might start in Michigan, get machined in Ontario, receive components in Ohio, return to Canada for sub-assembly, then come back to the U.S. for final vehicle integration.

Canada exported roughly C$60 billion in vehicles and auto parts to the U.S. annually in recent years[2]. Those exports include engines, transmissions, seats, electrical systems, and the myriad components that make modern vehicles run. U.S. factories depend on these parts as much as Canadian plants depend on U.S. components.

Building Materials: The Frame of American Housing

Canadian softwood lumber frames American homes. The U.S. imports billions of dollars worth of Canadian lumber annually, using it for residential construction framing, joists, and sheathing. Western Canadian provinces—British Columbia, Alberta—supply much of this timber from vast coniferous forests.

Even with existing antidumping and countervailing duties totaling around 14%[2], Canadian lumber remains cost-competitive and essential to U.S. homebuilders. Domestic U.S. lumber production exists but can’t meet current demand at competitive prices.

Beyond lumber, Canada supplies plywood, particleboard, and other wood products used in construction, furniture, and manufacturing[2]. The U.S. also imports significant quantities of aluminum and steel for construction—the same metals currently facing 50% Section 232 tariffs[2].

Food and Agriculture: From Farm to Table

The U.S. imports over $40 billion in Canadian agricultural and food products annually[6]. This isn’t exotic produce—it’s the everyday items Americans eat without thinking about origin.

Meat and livestock form a major category. Canada ships beef cattle and pork to U.S. processors, along with processed meat products ready for retail. Canadian beef integrates into the North American meat supply chain, with animals and cuts moving fluidly across the border based on processing capacity and demand.

Processed and packaged foods stock American grocery shelves. Canadian facilities produce snack foods, bakery products (breads, cookies, crackers), breakfast cereals, and confections sold under familiar U.S. brands[6]. Frozen foods—particularly french fries made from Canadian potatoes—supply both retail and foodservice markets.

Beverages include Canadian beer, whiskey, ice wine, and other alcoholic drinks popular in U.S. markets. Canadian breweries export both craft and mainstream brands southward.

Specialty items like maple syrup (Canada produces roughly 70% of global supply), canola oil, and certain grains round out the agricultural trade[6]. While individually small, these categories matter to specific U.S. industries and consumers.

Industrial Inputs: The Invisible Supply Chain

American manufacturing depends on Canadian inputs most consumers never see.

Critical minerals and metals include nickel (for stainless steel and batteries), cobalt (for lithium-ion batteries), potash (fertilizer), and uranium (nuclear fuel). Canada ranks as a top global producer of these commodities, with established trade relationships shipping them to U.S. manufacturers and utilities[2].

Aluminum from Canadian smelters becomes cans for beverages, components for aircraft and vehicles, and building materials. Even with 50% tariffs currently in place[2], Canadian aluminum remains integrated into U.S. supply chains because domestic production can’t meet demand.

Chemicals and plastics flow south for use in everything from cosmetics to packaging materials. Canadian petrochemical facilities produce inputs for U.S. manufacturing across multiple sectors.

Machinery and equipment—farm tractors, mining equipment, HVAC systems, industrial machinery—come from Canadian manufacturers serving North American markets. While consumers don’t buy these directly, the costs filter through to food prices (expensive farm equipment), construction costs (HVAC systems), and service prices.

The scale and diversity of U.S. Canada trade means tariffs don’t just hit one sector—they cascade through the entire economy, touching prices and supply chains in ways that often surprise consumers when they finally notice.

U.S Canada Tariffs, Where You’d Feel the Squeeze

A 100% tariff wouldn’t hit all at once like flipping a light switch, but within weeks to months, Americans would notice these pain points most acutely.

At the Gas Pump: Immediate Shock

Oil markets react to news, not just actual supply disruptions. The moment a 100% tariff on Canadian crude became credible, gasoline prices would climb. U.S. refineries—especially in the Midwest and Rockies—are configured for heavy Canadian crude. Switching sources takes time and money, costs that flow directly to fuel prices[5].

Even a 10% tariff on Canadian oil was estimated to cost U.S. consumers billions in the first year[5]. Scale that to 100%, and you’re looking at sustained price spikes at every pump in America. Heating bills would surge in states reliant on Canadian natural gas. Electricity rates would jump in regions importing Canadian hydropower.

Studies of the 2018-2019 China tariffs showed that import price increases passed through almost entirely to consumer prices[4]. For commodities like oil traded globally, pass-through tends to be even faster and more complete—expect pain within days of implementation.

Substitution difficulty: Very hard. Alternative heavy crude sources (Venezuela faces sanctions, Middle Eastern oil requires transport premiums and different refining configurations) can’t fill the gap overnight. The U.S. may be energy independent in aggregate, but specific refineries depend on specific crude grades[5].

On the Car Lot: Sticker Shock and Fewer Choices

Auto industry analysts warned that even a 25% tariff on North American auto trade could add roughly $3,000 to new car prices[7]. A 100% tariff could push increases well into five figures for some models before manufacturers absorb losses or halt production entirely.

Canadian-built vehicles—popular pickups, SUVs, sedans—would face the full brunt. Auto parts would cost double, raising repair bills and insurance premiums as parts scarcity drives up claims. Used car prices would climb as new inventory tightens and buyers delay purchases.

The integrated North American supply chain makes this especially painful. Parts don’t cross the border once—they ping-pong between U.S. and Canadian factories multiple times during production[7]. Each crossing under a 100% tariff regime stacks additional costs, compounding the final price tag in what trade experts call the “stacking effect.”

Research on the 2018 washing machine tariffs provides a preview: retail prices jumped roughly 12% to match the tariff rate within months[4]. The auto industry, with its complex supply chains, would likely see even larger disruptions and price increases under U.S. Canada tariffs of this magnitude.

Substitution difficulty. Retooling factories and reorganizing supply chains takes years, not months. Car shoppers would face higher prices across the board, even for non-Canadian vehicles, as domestic producers raise prices in a less competitive market.

At the Hardware Store: Housing Gets Pricier

Lumber prices already include roughly 14% in antidumping and countervailing duties on Canadian softwood[2]. Add 100% on top, and you’re looking at construction cost explosions that ripple through new home prices, renovation budgets, and eventually rent.

U.S. lumber capacity can’t meet current demand at existing prices. European and South American alternatives exist but cost more to transport and may not match quality or volume needs. Homebuilders would either raise prices, delay projects, or shrink home sizes to manage costs.

Steel and aluminum tariffs—currently 50% on Canadian metals[2]—already inflate costs for appliances, canned goods (aluminum for cans), and building materials. Doubling down would make everything from refrigerators to roof trusses more expensive.

Analysis of prior tariff episodes shows construction materials prices respond within weeks as existing inventory depletes and new, higher-cost shipments arrive[4]. Anyone building, buying, or renting would face higher costs as these input price increases work through the housing market.

Substitution difficulty. Expanding domestic sawmill capacity takes months to years. In the interim, construction costs rise and housing affordability worsens.

In the Grocery Aisle: Incremental Creep

Food price impacts would be more subtle but widespread. Canadian beef, pork, and processed foods supply U.S. retailers and restaurants. Snack foods, bakery products, and packaged goods would see price increases within weeks as existing inventory runs out and higher-cost shipments arrive[6].

Some items Americans might not connect to Canada—french fries from Canadian potatoes, certain breakfast cereals, specialty chocolates—would jump in price or disappear from shelves. Maple syrup, Canadian whiskey, and premium beers would become luxury purchases.

The bigger hit comes through inputs. Potash fertilizer from Canada (which accounts for ~80% of usage), facing tariffs, would raise costs for U.S. farmers, nudging up prices for domestically grown food over the following growing season. It’s a longer chain, but U.S. Canada tariffs on agricultural inputs eventually reach grocery bills.

Federal Reserve research on 2018-2019 tariffs found that consumer prices in affected categories rose notably compared to unaffected categories, with effects visible within months[4]. Food items would follow similar patterns under new tariffs.

Substitution difficulty: Moderate. The U.S. produces plenty of its own food and can source from other countries, but sudden shifts create short-term dislocations and higher costs during the adjustment.

The Hidden Tax: Everything Else Gets More Expensive

When transportation costs rise (fuel tariffs), construction slows (lumber tariffs), and manufacturing inputs cost more (metal tariffs), the entire economy reprices upward. Businesses facing squeezed margins raise prices where they can. Workers in affected industries—refineries, auto plants, construction—might see reduced hours or layoffs, dampening consumer spending power.

Economists who studied the 2018-2019 china tariffs found they raised overall consumer prices by about 0.5% relative to trend[9]—and those tariffs covered selected Chinese goods, not a comprehensive partner like Canada. The Peterson Institute estimated the full incidence fell on U.S. consumers and importers, reducing real income.

How Would Prices Actually Change With U.S Canada Tariffs: The Pass-Through Reality

Economic studies of the 2018-2019 trade war offer a preview of how U.S. Canada tariffs would affect consumers. When Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, U.S. import prices rose nearly one-to-one with the tariff rate[4]. Foreign exporters didn’t absorb the cost by cutting prices—American companies paid the full duty at the border.

Those costs then flowed to consumers. Washing machine prices jumped roughly 12% after tariffs hit, matching the duty rate[4]. Even untariffed dryers rose similarly as manufacturers capitalized on reduced competition. Furniture, household goods, and appliances all showed measurable price increases tied to tariffs.

A 100% tariff is four times larger than those test cases. While not every product would literally double in price—some imports would halt entirely, others would partially substitute—the economic consensus is clear: consumers bear the bulk of tariff costs through higher prices.

Federal Reserve researchers tracking tariffs in real-time found they passed through “fully and fairly quickly” to consumer prices in many categories[4]. Retailers initially tried tactics like front-loading inventory before tariffs hit and using promotions to smooth impacts, but within 6-12 months most of the tariff cost showed up in store prices.

Speed matters too. Commodity markets (oil, metals) react within days as traders anticipate costs. Consumer goods follow within weeks as inventory turns over. Durable goods like cars might have a month or two of buffer before new, higher-priced shipments arrive. But make no mistake—the clock starts ticking the moment U.S. Canada tariffs take effect.

Research consistently shows that for many goods, tariffs are largely passed through to consumer prices. Studies found near one-to-one cost pass-through at the border and significant pass-through to retail prices[4]. The Tax Foundation analysis estimated the 2018 tariffs raised average consumer prices by about 0.5% relative to trend[9]—and that covered a narrower range of goods than comprehensive tariffs on Canada would.

The Bottom Line: Integration Has a Price

The U.S. and Canada built one of the world’s most integrated binational economy over decades—oil pipelines running south, auto parts shuttling between factories, lumber framing houses on both sides of the border. That integration created efficiencies that kept costs down for consumers in both countries.

A 100% tariff would test those connections in ways the current tariff patchwork hasn’t. Gas prices, car costs, construction expenses, and grocery bills would all likely reflect the change, though the magnitude and speed would depend on how the tariff is structured and whether alternatives can fill gaps.

For American consumers, the key insight is straightforward: Canada’s exports often become American products. The oil gets refined into gasoline. The aluminum becomes beverage cans. The lumber frames new homes. Tariffs on those inputs don’t just affect Canadian producers—they ripple through to U.S. prices in ways that aren’t always obvious until the bills arrive.

Whether this tariff materializes or remains a negotiating position, it highlights how deeply North American supply chains interlock, and how quickly changes in trade policy can translate into changes at checkout counters.

References

[1] Reuters — Trump threatens Canada with 100% tariff over pending trade deal with China — Jan 24, 2026 — Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/trump-threatens-canada-with-100-tariff-over-possible-deal-with-china-2026-01-24/

[2] Congressional Research Service — U.S.-Canada Trade Relations (IF12595) — Dec 5, 2025 — Available at: https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/2025-12-05_IF12595_1f354ce3cecd196b31fad7a066a588ba2842374b.html

[3] Congress.gov (CRS) — U.S. Tariff Policy: Overview (IF11030) — Nov 2, 2025 — Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11030

[4] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis — What Have We Learned from the U.S. Tariff Increases of 2018-19? — May 2025 — Available at: https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2025/may/what-have-we-learned-us-tariff-increases-2018

[5] American Action Forum — U.S. Oil and Gas Tariffs on Canada and Mexico: What Are the Implications? — Mar 10, 2025 — Available at: https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/u-s-oil-and-gas-tariffs-on-canada-and-mexico-what-are-the-implications/

[6] USTR — Canada Trade Summary & USMCA — Accessed Jan 2026 — Available at: https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/americas/canada

[7] eMarketer — Tariffs on Canada, Mexico could crash the US auto industry — Feb 3, 2025 — Available at: https://www.emarketer.com/content/us-auto-industry-tariffs-north-american-supply-chain

[8] Government of Canada (Global Affairs) — Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement: Economic Impact Assessment — Feb 2020 — Available at: https://international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/cusma-usmca/analysis-analyse/impact-assessment-impact.aspx

[9] Tax Foundation — Trump Tariffs Raising Prices for Consumers — Oct 2019 — Available at: https://taxfoundation.org/blog/trump-tariffs-raise-prices-consumers/