In August 2023, Huawei released a smartphone that shattered every assumption about technology sanctions. The Mate 60 Pro contained a cutting-edge 7-nanometer chip — the exact technology U.S. lawmakers had spent years trying to keep out of Chinese hands.

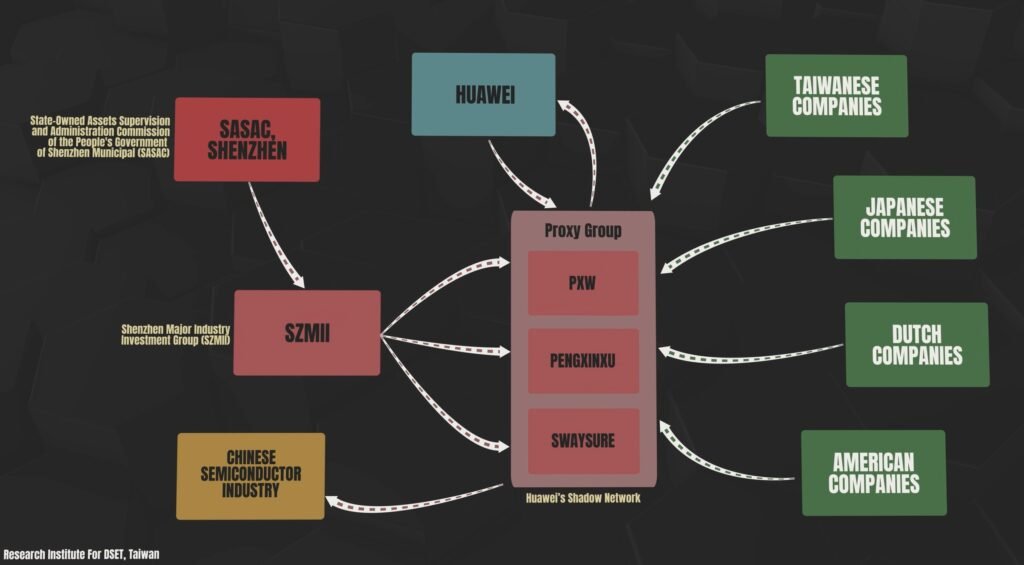

U.S. investigators traced the breakthrough to a web of obscure proxy companies. Each played a role in secretly funneling restricted semiconductor equipment through shell companies and intermediaries. They called it “a shadow supply chain network.”

But Huawei’s workaround was just one thread in a far larger web powering China’s Economy. Today, hundreds of billions of dollars in goods, technology, and resources move through invisible corridors that circle the globe, staying almost completely off the radar.

Welcome to China’s shadow Silk Road.

The Original Route, Reimagined

For centuries, the Silk Road connected China to the West through intermediaries and waypoints. Caravans crossed deserts, goods changed hands in distant markets, and empires enriched themselves through commerce that flowed along indirect paths.

History is repeating itself. But instead of caravans crossing deserts, we have container ships crossing oceans. But instead of silk, it’s semiconductors and rare earth minerals. And instead of visible trade routes, we have a sophisticated network designed to operate in the shadows.

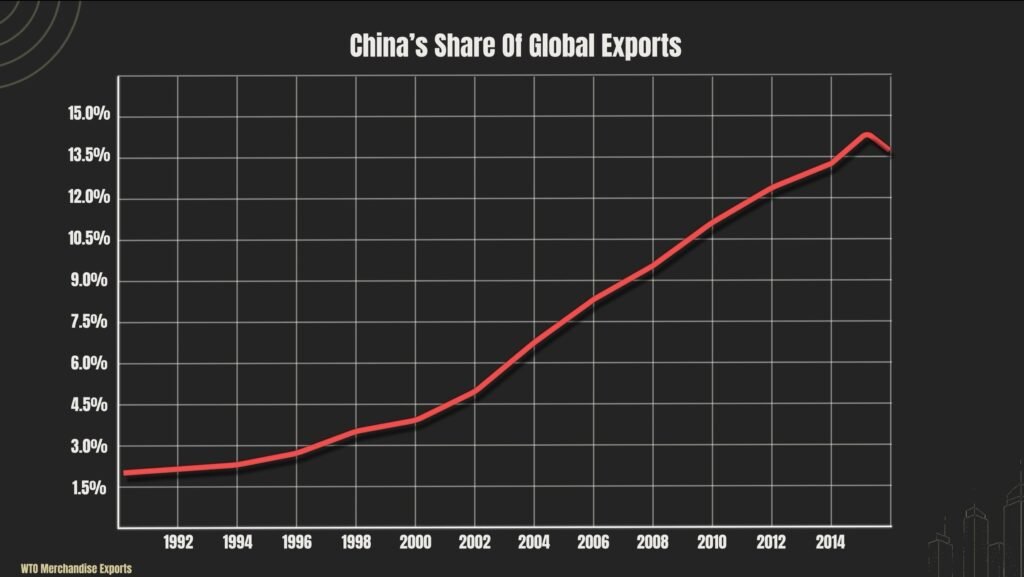

For three decades, China transformed into the world’s factory. By 2024, Chinese exports represented nearly one in every seven dollars of global export value. Western companies eagerly plugged into this system, chasing efficiency and rock-bottom costs.

When the World Blinked

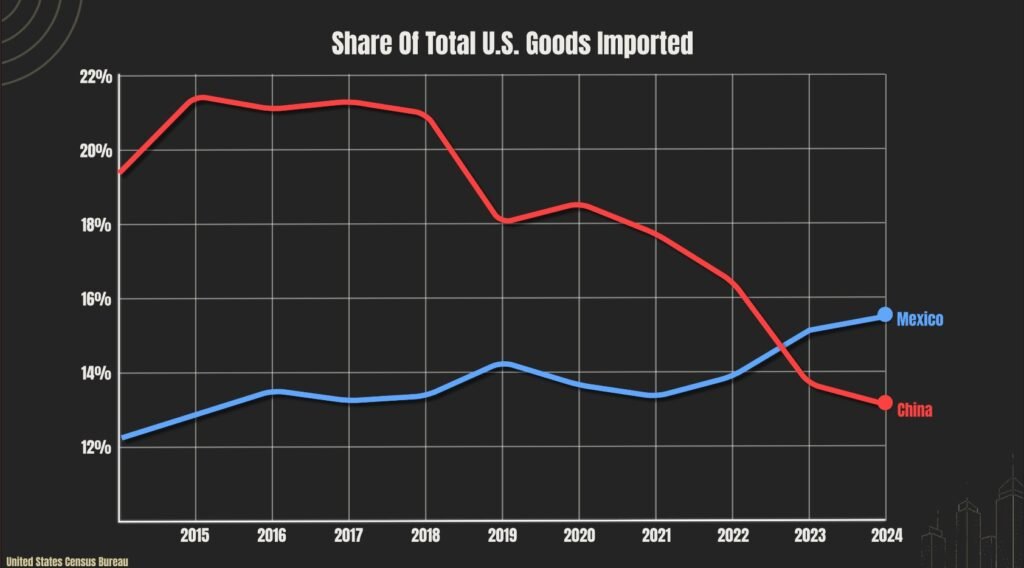

The breaking point arrived between 2018 and 2020. The U.S. launched a trade war, slapping tariffs on approximately $300 billion worth of Chinese goods and raising average import duties from roughly 3% to 19% by early 2020.

But COVID-19 delivered the knockout punch. Chinese factory lockdowns cascaded into global shortages. Companies discovered their supply chains were far more fragile than spreadsheets suggested. A toy factory in Ohio nearly shut down because it couldn’t get wheel axles from China. Auto plants went dark for lack of dollar sensors from Wuhan. Hospitals scrambled for masks.

The response was swift and predictable: diversification. Companies adopted “China plus one” strategies, building factories in Vietnam, India, and Mexico. By 2023, Mexico had overtaken China as America’s largest trading partner, accounting for about 15.4% of total U.S. goods trade.

Not quite. While companies were building new factories in “safe” countries, China was quietly building something else.

The Three Mechanisms of Invisibility Powering China’s Economy

China’s shadow supply chain operates through three distinct but interconnected methods. Each exploits different gaps in the global trading system.

1. The Proxy Network

When Washington blacklisted Huawei in 2019, the company didn’t disappear. It evolved.

A Shenzhen government fund backed new chipmakers — firms like SwaySure and Pengxinxu — set up specifically to fill gaps left by U.S. export bans. These shadow companies exploited three critical vulnerabilities: timing gaps in international sanctions alignment, geography gaps using brokers in Singapore and Malaysia, and definition gaps that let them acquire services and technical know-how even when hardware was banned.

The scale is staggering. Despite export controls, China imported nearly $40 billion worth of chip-fabrication equipment in 2023 alone.

When U.S. expanded export restrictions on chipmaking tools in 2022, it took Japan and the Netherlands nearly two years to match those rules. That delay created a window. Chinese proxy companies rushed through it, legally purchasing equipment that would soon be banned.

The proxy network doesn’t just operate in semiconductors. It’s a template that works across industries, from pharmaceuticals to rare earth minerals.

2. Origin Laundering

In 2012, the U.S. imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels to protect domestic manufacturers. Direct imports from China declined. But cheap solar panels kept flooding American markets anyway.

By 2022, investigators discovered the truth: four Southeast Asian countries supplied 80% of America’s solar panels, but Commerce Department investigations revealed these were actually Chinese panels, simply assembled in Malaysia or Vietnam to dodge tariffs.

The pattern repeats across industries. Graphite refined in China ships to India for minimal processing, then gets labeled “Indian.” Lithium hydroxide from China routes through South Korea before hitting European shores. Chinese electronics plants in Mexico assemble products for the U.S. market using components still manufactured in Shenzhen.

Mexico’s tech exports to the U.S. jumped from $60 billion to $102 billion since 2018, yet much of the value still comes from imported parts, many sourced from Asia and often from China itself.

The “Made in Vietnam” label often masks a product that’s 80% Chinese, with only final assembly happening in Hanoi.

3. The Dark Fleet

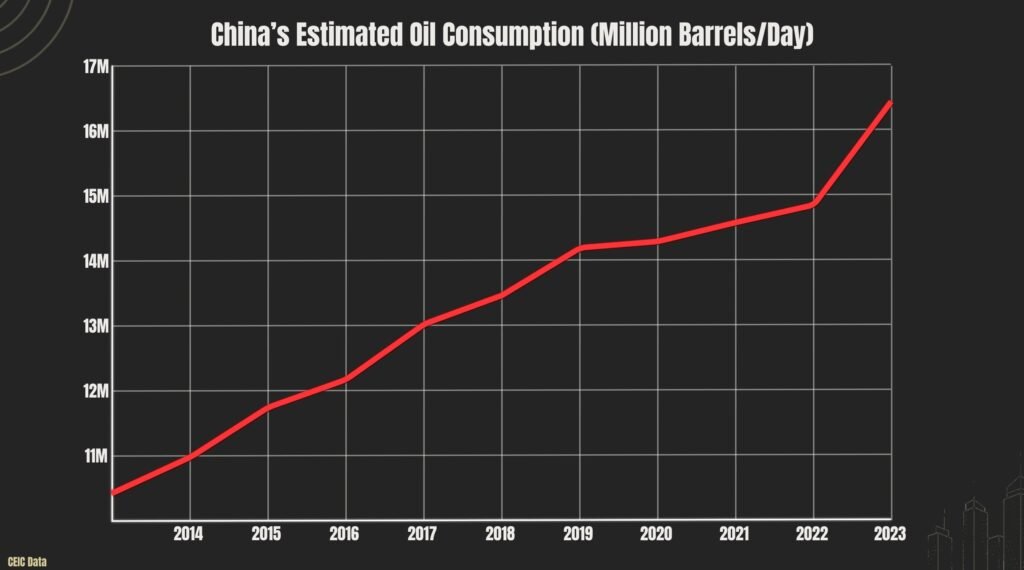

China imports over 70% of its oil, making it vulnerable to Western financial systems that dominate global energy trade. The solution? Buy from sanctioned sellers — Iran, Venezuela, Russia — at steep discounts, using ships that operate in regulatory grey zones.

These vessels employ sophisticated tactics: reflagging under countries with looser rules, disabling or spoofing GPS transponders to disappear from public trackers, and conducting ship-to-ship transfers in international waters to obscure cargo origins.

A Reuters investigation revealed how the tanker Wen Yao broadcast its location off Brazil while satellite data showed it was actually thousands of miles away at Venezuela’s José Terminal, loading crude. After securing the oil, the ship spoofed its signal again before finally revealing its true position en route to China.

The number of shadow vessels increased from 97 to over 3,000 between 2022 and 2024. In 2023, Iran moved an estimated $50 billion in crude this way, with almost 90 percent bound for China.

The Sectors Most Exposed

Not all industries face equal risk from China’s shadow supply chain. Some sectors are deeply entangled; others have managed to maintain independence.

High-Risk Sectors

Technology and semiconductors top the vulnerability list. China’s Ministry of Commerce announced export restrictions on gallium, germanium, and antimony in December 2024, targeting minerals critical to chip production. China produces 90% of the world’s primary gallium production.

Western tech companies face a difficult reality: even when they source from “friendly” countries, Chinese inputs often lurk several layers deep in the supply chain.

Electric vehicles and batteries present similar challenges. China refines roughly 70% of cobalt and 90% of graphite globally. When manufacturers build “European” or “American” batteries, they’re often using Chinese-refined materials that have been routed through third countries.

Chinese firms like CATL and BYD haven’t just dominated battery production. They’ve set up plants in Hungary, Thailand, and Morocco specifically to funnel Chinese-made cells and materials into products labeled “Made in Europe” or “Made in USA.”

Pharmaceuticals carry hidden dependencies that few consumers understand. An estimated 90% of U.S. antibiotics rely on Chinese-made active pharmaceutical ingredients. During COVID-19, these vulnerabilities became painfully visible when Chinese plant closures rippled into medicine shortages worldwide.

Energy and commodities operate through the dark fleet networks described earlier. In 2025, China implemented further export controls on rare earth elements used in everything from wind turbines to defense systems, creating immediate supply disruptions for Western manufacturers.

Lower-Risk Sectors

Defense and aerospace have deliberately minimized Chinese dependencies for security reasons. Military supply chains in the U.S. and allied countries source critical components domestically or from trusted partners. But even here, vulnerabilities exist — rare earth materials for specialized alloys remain a concern.

Agriculture and food supply chains tend to be more locally focused or globally diversified, with less direct reliance on China for staple crops. The exceptions are specialized inputs like certain vitamins, fertilizers, and agrochemicals where China maintains significant market share.

Professional services — software development, finance, consulting — operate largely independent of physical Chinese supply chains, though they’re not immune to broader market disruptions affecting their clients.

The Counter-Offensive

Western economies aren’t standing idle. A new toolkit is taking shape to combat shadow supply chains.

Sealing the Tech Leaks

The U.S., Japan, and Netherlands have aligned export-control lists for chip-making tools. Licenses now follow equipment — if a machine is resold to a shell company, both seller and end-user face penalties.

U.S. Customs is piloting AI-powered supply chain traceability tools that use artificial intelligence to map products from raw material to final good, allowing customs to identify if a shipment from Vietnam actually contains Chinese-origin components subject to duties.

Policing the Seas

U.S. Treasury and UK sanctions offices are blacklisting ships that spoof GPS or trade oil mid-sea. Once flagged, London-based insurers must cancel coverage, leaving those tankers unable to dock or refuel.

Satellite-data firms feed enforcement dashboards used by sanctions investigators, making it harder for dark fleets to operate undetected.

Tracking Supply Chains

Europe’s new Battery Regulation will require every EV and industrial battery to carry a digital passport revealing where its lithium, nickel, and graphite were mined and refined.

Customs agencies are using AI mapping tools to link shipping and supplier data, exposing Chinese components hidden inside products labeled “Made in Vietnam” or “Made in Mexico.”

The Stakes

This isn’t just about trade statistics. China’s shadow supply chain represents a fundamental challenge to the sanctions system meant to keep advanced tech and energy out of adversaries’ hands.

In December 2024, China banned exports of critical minerals to the U.S. in retaliation for American chip restrictions, sending shockwaves through the global semiconductor industry and raising concerns about supply chain disruptions and price increases.

By October 2025, China had escalated controls to include products and components containing Chinese-sourced rare earth materials, even if traded domestically in other countries. Many carmakers in the United States and Europe struggled to obtain permanent magnets, with some forced to temporarily shut down facilities.

The implications extend beyond economics into national security. Western defense contractors discovered their weapons systems relied on Chinese rare earth elements for components. European rearmament efforts faced immediate bottlenecks when China tightened export controls.

Mexico remains America’s top trade partner for the third year in a row, but only 80% of U.S. companies with operations in China reported profitability in the past year, and 43% have adjusted their supplier or sourcing strategies.

Companies face a difficult choice: accept higher costs and slower innovation to build resilience, or maintain efficiency while accepting geopolitical risk.

The New Geography of Trade

A new map is emerging. We can call it Silk Road 2.0 — a web of corridors spanning the Americas and Asia that frequently loops back into China’s Economy in less obvious ways.

Pan-American supply chains are integrating more tightly. The U.S., Mexico, and Canada form the core, with goods flowing tariff-free under USMCA. But Chinese investment in Latin American infrastructure and mines means even “American” supply chains often depend on Chinese capital upstream.

Asia’s production network is fragmenting across Vietnam, Thailand, India, and Indonesia. But China often remains the source of industrial machinery and base materials these factories use. The final assembly happens elsewhere; the critical inputs still come from China.

Digital corridors are equally important. China’s Digital Silk Road initiative invests in telecommunications infrastructure — from fiber-optic cables to 5G networks — across Belt and Road countries. In the future, data itself becomes a trade commodity, and China aims to channel those flows through its equipment.

Looking Ahead

The original Silk Road lasted 1,400 years not because it was direct, but because it was adaptable. When one route closed, merchants found another. When one kingdom fell, caravans shifted.

China’s shadow Silk Road operates on the same timeless principle. Every time the West tightens controls, China finds another route. Tariffs push factories to Vietnam. Sanctions build proxy networks. Energy bans give rise to ghost fleets.

Despite tariff threats, two-thirds of companies plan to maintain or expand business with China in 2025, recognizing the practical reality that alternative supply sources take years to develop.

The harder regulators try to contain it, the more the system adapts. That’s the real power of the shadow Silk Road.

Western efforts to build transparency through AI tracking, digital passports, and stricter enforcement are genuine. But they face a fundamental challenge: the economic incentives to use shadow routes remain powerful. Chinese materials and factories are often the cheapest or most capable option, and companies facing profit pressures will be tempted to use indirect sourcing.

We may be heading toward a bifurcated trading system — one sphere where transparency is enforced by aligned nations, and another shadow sphere where China and its partners trade through their own channels, possibly using alternative currencies or blockchain systems to avoid detection.

For businesses, the lesson is clear: visibility matters more than ever. Companies need to know not just their immediate suppliers, but multiple tiers deep into their supply chain. The “Made in Vietnam” label means nothing without understanding what percentage of that product’s value comes from Chinese inputs.

The shadow Silk Road reveals something fundamental about our global economy: supply chains are more than logistics. They’re expressions of power, strategy, and adaptability. China has built a system that ensures its role in the globe remains essential even when it’s invisible.

References:

[1] Tekedia – “U.S. Lawmakers Warn $40bn in Loopholes Are Undermining Global Chip Export Controls on China” (2024) – Available at: https://www.tekedia.com/u-s-lawmakers-warn-40bn-in-loopholes-are-undermining-global-chip-export-controls-on-china/

[2] Research Institute for Democracy, Society and Emerging Technology – “DSET Releases Latest Report, Uncovering Huawei’s Shadow Network and Shenzhen’s Semiconductor Investment Strategy” (2024) – Available at: https://dset.tw/en/publication-en/00094/

[3] Reuters – “How Iran moves sanctioned oil around the world” (2024) – Available at: https://www.reuters.com/graphics/IRAN-OIL/zjpqngedmvx/

[4] Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas – “China remains modest player in U.S.-Mexico trade despite growing scrutiny” (2025) – Available at: https://www.dallasfed.org/research/pubs/25trade/a1

[5] Smart Import and Customs – “China’s Raw Material Export Restrictions: A Comprehensive Overview” (December 2024) – Available at: https://smartimport.co/chinas-raw-material-export-restrictions/

[6] International Energy Agency – “China’s restriction on critical mineral exports to the United States” (December 2024) – Available at: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/china-s-restriction-on-critical-mineral-exports-to-the-united-states

[7] QIMA – “2025 Global Supply Chain Trends: Adapting to Disruption” (2025) – Available at: https://www.qima.com/supply-chain-trends

[8] Optilogic – “China Supply Chain Issues: Navigating the Complexities” (2025) – Available at: https://www.optilogic.com/blog/china-supply-chain-issues