In March 2025, former President Donald Trump made headlines by announcing sweeping new auto tariffs—a 25% import tax on foreign-made vehicles and select auto parts. The move has sent shockwaves through global automakers, Wall Street, and trade partners, marking a sharp shift in U.S. trade policy.

These tariffs, set to take effect in April and May 2025, are among the most aggressive actions taken in the automotive sector in decades. In this article, we’ll break down the reasoning behind the new tariffs, how they compare to Trump’s first term, which carmakers are most affected, and what the broader economic implications are for domestic car production in the U.S.

We’ll also explore one overlooked consequence of the tariffs that few analysts are talking about—and why it could reshape the industry more than anything else.

What Are Trump’s New Auto Tariffs?

Trump’s latest auto tariffs impose a 25% duty on all imported passenger vehicles, including sedans, SUVs, trucks, and crossovers. Additionally, a wide range of imported auto parts—such as engines, transmissions, and electronic components—will also be taxed at 25%.

-

Vehicle tariffs begin April 3, 2025

-

Auto parts tariffs begin May 3, 2025

This is not just a symbolic gesture. The administration projects that these tariffs will generate over $100 billion annually in new revenue, while simultaneously pushing automakers to relocate production to U.S. soil.

What’s Different From Trump’s First Term?

During Trump’s first term (2017–2021), he frequently threatened auto tariffs but stopped short of implementing them. His administration launched a Section 232 investigation in 2018, which concluded that auto imports posed a national security threat. However, instead of acting on it, Trump used the threat of tariffs as a negotiating tool with Japan, the EU, and other trade partners.

He did impose steel and aluminum tariffs in 2018, which impacted auto production costs indirectly. But auto tariffs themselves were never enacted.

In 2025, the gloves are off. Trump is no longer using tariffs as a bluff—he’s using them as policy. The key difference is that now, he believes automakers failed to follow through on their first-term promises to increase domestic production.

Why Trump Is Implementing Auto Tariffs Now

The Trump administration justifies the tariffs based on national security concerns and a lack of progress in reshoring automotive production. Here’s the core argument:

-

In 2024, 16 million light vehicles were sold in the U.S.

-

8 million of those vehicles were imported—a 50% share.

-

Even the 8 million vehicles built in the U.S. often have only 40–50% domestic parts content.

-

That means only about 25% of total U.S. vehicle consumption is truly American-made.

The White House argues that this level of foreign dependency makes the U.S. vulnerable to global supply chain disruptions and economic coercion. The tariffs aim to penalize offshoring and reward domestic production, effectively forcing automakers to “build where they sell.”

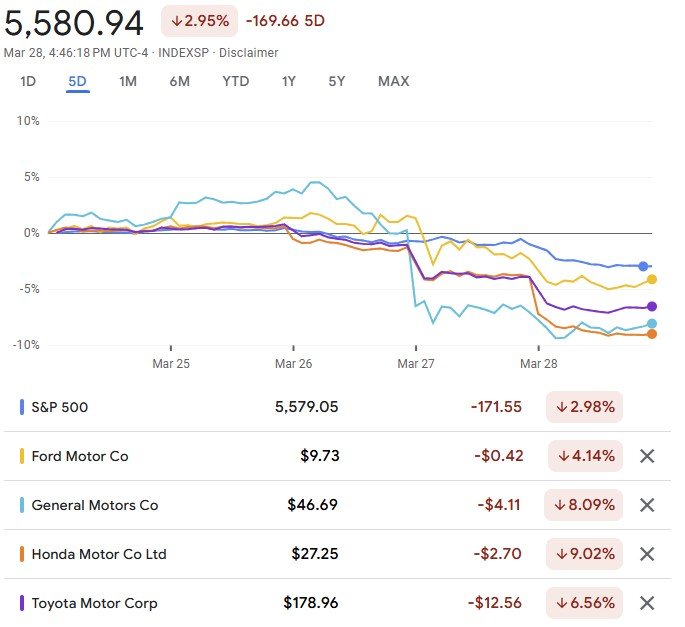

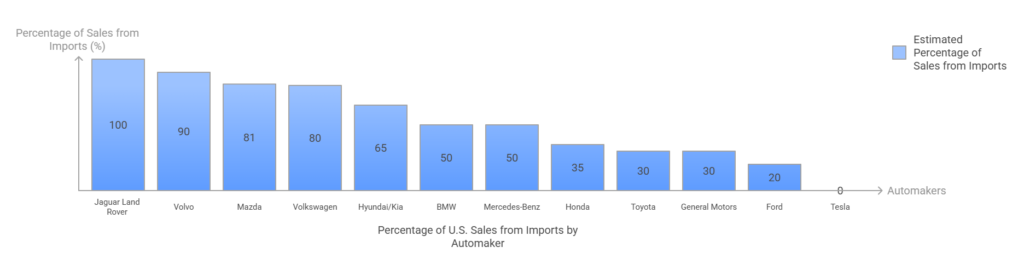

Who Are the Most Impacted Automakers?

Not all automakers will feel the tariffs equally. Companies with high import dependency and limited U.S. manufacturing will bear the brunt.

| Automaker | % of U.S. Sales from Imports | Domestic Assembly? | Key Models Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jaguar Land Rover | 100% | ❌ None | Range Rover, Defender |

| Volvo (Geely) | 90% | ⚠️ Limited | XC60, S90 |

| Mazda | 81% | ❌ None | CX-5, Mazda3 |

| Volkswagen | 80% | ✅ (Chattanooga) | Golf, Tiguan |

| Hyundai/Kia | 65% | ✅ (AL, GA) | Elantra, Sorento |

These brands will either pass the 25% cost increase on to consumers—raising car prices by $3,500 to $12,000—or absorb the hit to margins, which is unlikely.

For example, Jaguar Land Rover sells zero vehicles made in the U.S. That’s a straight 25% cost hike across their entire catalog.

Who Is Least Affected?

| Automaker | % U.S.-Built Vehicles | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tesla | 100% | All U.S. production, vertically integrated supply chain |

| Ford | ~70% | Major U.S. factories; some imports for small cars |

| Honda | ~65% | Robust U.S. plants in Ohio, Indiana, Alabama |

| Toyota | ~50% | Strong U.S. presence (e.g., Kentucky, Texas plants) |

Tesla is the clearest winner here. It builds every vehicle in the U.S. and sources many parts domestically. Ford and Honda also benefit, but both still import critical components.

The Hidden Tariff: Auto Parts

While the spotlight is on foreign-built vehicles, the tariffs on imported auto parts may have an even wider ripple effect. Many vehicles assembled in the U.S. still rely heavily on components from abroad.

- Transmissions from Japan

- Electronic modules from China

- Engines from Mexico and South Korea

This means that even domestically assembled cars could see cost increases of $1,000–$2,000 per unit due to more expensive parts. General Motors and Ford, despite their large U.S. footprints, source parts from over a dozen countries.

🧩 Automakers Most Reliant on Imported Parts (for U.S. Assembly)

| Automaker | Notable Imports | U.S. Assembly Footprint | Notes |

| GM | Engines (Mexico, China), electronics (Asia) | High (MI, OH, TX) | Large U.S. operations, globally sourced |

| Ford | Powertrains (Mexico), electronics (EU/Asia) | High (MI, KY, MO) | Heavy truck/SUV U.S. focus |

| Toyota | Transmissions (Japan), sensors (Asia) | Medium-High (KY, TX, IN) | Balanced global-local supply chain |

| Honda | Engines (Japan), electronics (China) | High (OH, AL, IN) | U.S. leader in local sourcing |

| Hyundai/Kia | Engines and parts (Korea) | Medium (AL, GA) | Strong Korean import dependency |

| BMW/Mercedes | Engines, transmissions (Germany) | Medium (SC, AL) | U.S. plants rely on EU components |

Even automakers with extensive U.S. production cannot escape global sourcing. The more parts they import, the more they’ll feel the pain of component-specific tariffs in addition to finished vehicle duties.

The Economics of U.S. Car Production vs Imports

Understanding the economics helps illustrate why automakers rely so heavily on imports:

🚗 Cost Breakdown: Imported vs Domestic

| Cost Category | Imported Vehicle | U.S.-Built Vehicle (with foreign parts) |

|---|---|---|

| Base Production | $20,000 | $24,000 |

| Logistics | $2,000 | $1,000 |

| Tariffs (New) | $5,500 | $1,500 (parts only) |

| Final Retail Cost | $27,500 | $26,500 |

Before the tariffs, import-based models had a cost edge. Now, domestic production becomes slightly more cost-competitive—but only if automakers localize parts production too.

What Everyone Is Missing: The Supply Chain Time Bomb

While most headlines focus on consumer prices and corporate margins, a deeper issue lurks beneath the surface: the fragility of the U.S. automotive supply chain.

- The U.S. still imports 60% of its aluminum and about 15% of its auto-grade steel, both now subject to revived Trump-era tariffs (25% on steel, 10% on aluminum). This raises costs for automakers regardless of where they build vehicles, since U.S.-based plants also depend on imported metals.

- Many critical components—like semiconductors, battery cells, and wiring harnesses—have no large-scale domestic production. Even for cars assembled in the U.S., these parts often come from abroad.

- Rebuilding the supply chain isn’t quick or easy. Automakers depend on Tier 1 suppliers for full systems (e.g., steering, braking), and Tier 2 suppliers for the smaller parts that go into those systems. If either tier breaks, so does production.

Bottom line: tariffs are pushing costs up in a system that’s already stretched thin. A missing $15 part can halt the production of a $50,000 vehicle—highlighting just how exposed the entire supply chain really is.

Policy Whiplash: How Uncertainty Is Hurting Business

Beyond the material impact of tariffs themselves, one of the biggest pain points for automakers and suppliers is the ongoing policy uncertainty. The shift from one administration’s trade stance to another—often with dramatic reversals—makes long-term investment planning extremely difficult.

Many automakers are hesitant to commit billions of dollars to new U.S. factories or supply chains if future administrations might reverse course. For example, after Trump’s first-term tariff threats, some companies began reshoring, only to see the Biden administration scale back tariff enforcement. Now in Trump’s second term, policy has reversed again—hard.

This start-stop cycle has created a climate of unpredictability that businesses dislike even more than tough regulations. Automakers require 5–10 years of planning for major capital investments. When trade policy changes every 4 years, it undermines confidence and deters bold moves toward domestic production.

Until there’s more continuity or bipartisan consensus around trade strategy, the policy volatility itself becomes a hidden tax on industry progress.

Will the Auto Tariffs Work?

Whether the auto tariffs “work” depends on how success is defined. If the goal is to boost U.S. auto production, the tariffs may nudge some progress—but the outcome won’t be immediate.

During Trump’s first term, although no auto tariffs were actually implemented, the threat of them prompted companies like Toyota, Mazda, and BMW to announce new U.S. investments. However, most of those expansions yielded only modest production increases. For instance, the joint Toyota-Mazda plant in Alabama added just 150,000 units per year—under 1% of U.S. light vehicle sales—and BMW’s SUV-focused growth didn’t reduce its overall reliance on imports. The current tariffs are a firmer push to shift manufacturing stateside.

Some automakers are better positioned than others. Tesla and Ford, with strong domestic output, may fare well. Honda and Toyota could become more competitive if they localize more of their parts supply. But for companies with limited U.S. presence, the short-term effects will likely include:

- Higher vehicle prices — pushing car ownership out of reach for some consumers and dampening broader spending across the economy.

- Tighter profit margins — most automakers operate on 3–8% net margins. A 25% tariff on vehicles or key parts could wipe those out entirely. Smaller brands like Mazda, Volvo, and Jaguar Land Rover, and even debt-heavy giants like GM and Ford, may lack the capital to shift production quickly.

- Disrupted dealer networks — inconsistent inventory and delivery delays could hurt dealerships, especially smaller ones reliant on imports.

- Retaliatory trade actions — key trade partners are preparing countermeasures. Trump has signaled he’ll respond to foreign tariffs with more U.S. tariffs, setting the stage for a trade spiral that could affect industries beyond autos.

As Trump reasserts tariffs as a central part of his second-term strategy, how the public perceives this approach—economic protectionism vs. self-inflicted pain—will shape its political and economic legacy.

Final Thoughts: The Road Ahead

Trump’s auto tariffs mark a bold new chapter in U.S. trade and industrial policy. Unlike the threats of his first term, this time the tariffs are real—and the consequences are already rippling through the global automotive industry.

Some automakers—like Tesla, Ford, and Honda—may be relatively insulated due to strong domestic production. Others—such as Jaguar Land Rover, Mazda, and Volvo—face significant disruption, given their reliance on imports and limited U.S. assembly capacity.

But this isn’t just about where final assembly occurs. The deeper challenge is the entire automotive supply chain. From imported aluminum and steel to foreign-made semiconductors and transmissions, even “Made in America” cars are often built with globally sourced parts. The tariffs on auto parts, steel, and aluminum expose just how interwoven the industry has become—and how costly it will be to untangle.

Ultimately, these tariffs are designed to force a long-term industrial realignment. Whether that results in revitalized U.S. manufacturing or higher costs for consumers depends on whether automakers can genuinely invest in—and rebuild—domestic supply chains. Until then, both the benefits and burdens of this policy will be unevenly distributed across the industry.